President Barack Obama

Truth – and Consequences

The vast majority of Americans appear to have re-learned the long-standing political dictum, “Elections have consequences.” Voters turned out in record numbers for last month’s mid-term elections – not just those determined to send a message of “resistance” to President Donald Trump, but also those signaling their support. The run-up to and aftermath of these elections offered numerous opportunities for commentary online, in print, live, and on TV. So, in this update I’m providing a (multimedia!) synthesis:

The vast majority of Americans appear to have re-learned the long-standing political dictum, “Elections have consequences.” Voters turned out in record numbers for last month’s mid-term elections – not just those determined to send a message of “resistance” to President Donald Trump, but also those signaling their support. The run-up to and aftermath of these elections offered numerous opportunities for commentary online, in print, live, and on TV. So, in this update I’m providing a (multimedia!) synthesis:

The country is divided between those who benefit from the global, digital economy, and those who don’t.

The Rome, Italy, branch of the Aspen Institute unveiled its new-and-improved website the day before the election, and its launch prominently featured my piece, Two Americas and the lost center, which concluded:

The Rome, Italy, branch of the Aspen Institute unveiled its new-and-improved website the day before the election, and its launch prominently featured my piece, Two Americas and the lost center, which concluded:

One of these two nations clearly was winning the economic, cultural and political wars until recently; the other has predictably struck back with a vengeance. Both now believe, probably correctly, that they are in an existential struggle with the other where only one will survive.

There are, in short, two sides – but no center.

Democrats and progressives should be – but are not effectively – addressing the concerns of those left behind in this economy.

The weekend before the election, I was visited at my home by Bruce Hawker, a correspondent and producer for Australian TV traveling the US in the weeks leading up to the midterm election.

We’ll have to wait until early 2019, when Bruce’s documentary airs in Australia, to see exactly what I said (even I don’t recall). But I spoke on the same general theme a few days earlier at the University of Scranton, where I explained, in response to one question, my concern with progressives’ failure to address the economic anxieties of Trump voters. (As a bonus, here’s my 3-minute explanation of blockchain.)

Disaffected and economically disfranchised Americans have risen in revolt and seized political power on behalf of an illiberal and undemocratic ideology.

I wrote this piece for Aspenia Online, All Globalists Now, just after the election in response to President Trump’s closing theme framing the country’s choice as one between “nationalism” and “globalism”:

In sum, the supposedly-nationalist and anti-globalist movement is in fact global in scope and and transnational in organization. The foreign regimes that serve as its models and allies are the most violative of any today of the sovereignty and internal integrity of others. Their national cheerleaders, however, welcome these international models not only to guide but also, if necessary, to override US institutions in constructing a similar “nationalism”.

In sum, the supposedly-nationalist and anti-globalist movement is in fact global in scope and and transnational in organization. The foreign regimes that serve as its models and allies are the most violative of any today of the sovereignty and internal integrity of others. Their national cheerleaders, however, welcome these international models not only to guide but also, if necessary, to override US institutions in constructing a similar “nationalism”.

The print version of Aspenia is republishing this month my piece, Urbi et Orbi – previously published only in Italian – which similarly observes:

The tripartite division between producers, transformers and predators described above generated the same dynamic that we see in today’s populism, with the left trying to appeal to an urban middle class against an economically and politically predatory elite, with the conservative wing of that elite appealing, usually more successfully, to the producers in the exurban extractive economy by attacking the allegedly-parasitical professional classes.

The tripartite division between producers, transformers and predators described above generated the same dynamic that we see in today’s populism, with the left trying to appeal to an urban middle class against an economically and politically predatory elite, with the conservative wing of that elite appealing, usually more successfully, to the producers in the exurban extractive economy by attacking the allegedly-parasitical professional classes.

Not surprisingly, this illiberal, anti-democratic movement is gaining and holding power by suppressing the exercise of democracy. My CNN debut came in this piece critiquing the Republicans’ increasing reliance on voter suppression as a means of holding onto power:

As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg trenchantly observed in her dissent, however, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” It’s now also clear, to continue Ginsburg’s metaphor, that putting your umbrella away when it’s not raining, as Roberts would have it, is usually sufficient itself to provoke a cloudburst.

The majority of Americans, who are basically doing well, reject this ideology. History is on their side – but the country’s future could still go either way.

In The Wave Election, to be published by Aspenia later this month, I argue that “there is a slow-moving tide of history of which today’s events are merely a part – perhaps a frothing bubble, perhaps a cresting whitecap, on a larger, longer, slowly rolling wave.” The piece concludes with this warning:

The Trump phenomenon represents a powerful undertow running counter to the tide of history – a xenophobic reaction to an America moving in a more socially-liberal, more technology-centered, more globally-integrated and multicultural direction. That tide will keep rolling in, on larger and larger waves. But the undertow is always there, and can be deadly if you don’t pay it proper respect.

In the short term, I still give Trump a slightly better than 50-50 shot at re-election.

The day before the election, I moderated a panel of international experts in DC – as I had two years ago – to discuss what our election meant to others around the world. Virtually none of the foreign visitors in attendance expected Trump to be re-elected – while I did.

What do you think? As always, I look forward to your comments below.

And please check out the second annual Greater Good Gathering that I’m organizing in February in conjunction with Columbia University, Union Theological Seminary, and the American Academy of Political Science. Focusing on the ways that technology today can threaten a shared sense of “community” and the common good – or fulfill its original promise to help build them – the conference will feature tech executives, prominent journalists, leading academics on all aspects of the tech revolution from dating apps to cyber war, and top officials from the Bush, Obama and Trump Administrations. Register today, and spread the word!

“Are You Better Off?”

I just wanted to share with you my most recent piece for US News & World Report, which is also, sadly, my last, as they’ve discontinued their Opinion section. Watch for news on my new writing outlets soon.

I just wanted to share with you my most recent piece for US News & World Report, which is also, sadly, my last, as they’ve discontinued their Opinion section. Watch for news on my new writing outlets soon.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP last week launched an international trade war, hung up on Mexico’s president because he wouldn’t agree to pay for Trump’s border wall and announced he favored seizing guns without due process (a position from which he quickly retreated). These issues all have something in common (other than Trump) that goes to the root of what’s wrong in American politics today.

As discussed (here and here) during the 2016 campaign, both trade and immigration constitute a particular type of problem: Each benefits the larger society, raising the standard of living not just of the country as a whole but also of the majority within it. Yet both produce losers; various studies show, for instance, that immigration results in higher earnings for those with already-higher earnings – but lower wages for the lower-skilled.

Such “wedge issues” are used by politicians to drive Americans apart to the advantage of no one but these politicians. They are a means to exploit people’s misfortune by turning it into anger – and then turning that anger into votes. What they are not are exercises in building constructive solutions to problems, through compromise, consensus or common cause. And they are all traceable to the single watershed moment in which Ronald Reagan transformed American politics into the unrelenting exercise in selfishness that it is still today, when he asked Americans to vote on the basis of one question alone: Are you – not the country as a whole, or others, but you – better off today than you were four years ago?

Yes, politics is largely about self-interest, and even the Framers believed that a balance of self-interests, not messianic utopianism, was the central requirement of stable democracy. But the country’s leaders used to call us to a vision – even when the ultimate goal was individual freedom and self-realization – of an America greater than each of us individually. “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” died with “Are you better off?”

Trump is the apotheosis of this morally-denuded politics. Has there ever been a human being so clearly interested in nothing but himself? Despite his faux populism, his agenda in office has been a mix of standard-issue tax breaks targeted almost entirely to his fellow plutocrats and banana-republic self-enrichment. Even his conception of “making America great again” is about atomized self-interests, not any notion of an “America” embracing all, or even most, of us, knit together to form a society: A “greater good” beyond individual grievance? Global leadership? Moral values? As Robert D. Kaplan recent wrote in The National Interest (by no means a liberal publication), “[Trump] has also, with his calls for protectionism and a narrowly defined American self-interest, voided American foreign policy of any real, uplifting purpose – another sure sign of decline.” We are, in short, a country losing its way morally, one wallowing wholly in self-interest.

Whatever Trumpism’s underlying themes of racial, sexual and economic resentments, Trump has chosen trade, immigration and the demise of extractive industries as his chisels to break apart American society precisely because, while these have generated tremendous gains for the U.S. as a whole, they produce a subset who pay the price for the overall advance. Morality – as well as a practical regard for political reality and social peace – suggests that some of the gains of progress be redistributed to its victims; this might, in fact, be regarded as the core of “progressivism.” But as Democrats have become the “Party of the Ascendant,” those left behind by the world economy – largely older, white, religious, conservative males with lower levels of education living in rural or exurban areas – don’t seem all that appealing, or deserving of solicitousness, to “progressives” nowadays. In lieu of adequate solutions, Trumpism has been left to exploit the resulting unfairness and resentment to tear down both broader progress and all social cohesion.

This is exemplified in the current polarization over guns, as well, a point brought home by a Douglas High School student, Emma Gonzalez. Toward the end of her fiery speech with its refrain, “We call B.S.,” Gonzalez observed that the position of gun advocates appears to be that their rights to own guns outweigh children’s right to live. This has been a recurrent liberal argument since the Parkland shootings – but liberals ought to be wary of assertions that all rights must be balanced against other concerns: The rights to a fair trial, or against cruel and unusual punishment, or to free speech simply are not outweighed by governmental exigency or others’ sensitivities. Nonetheless, as I wrote after these shootings, most of us recognize and voluntarily concede non-governmental restraints on our rights in order to live in, and help produce, a functioning society with others. It’s called decency.

What’s striking about the gun debate today is the absolute unwillingness to seek the kinds of compromise necessary to a society, as opposed to an unwilling collection of individuals. We are no longer interested in anyone else’s perspective or anyone else’s rights. As Gonzalez summed up the situation, dismissively, “Mine! Mine! Mine! Mine!”

This phenomenon isn’t helped by Trump’s suddenly announcing that, as on so many other issues, the answer is to empower his own id and worry about constitutional rights later, if at all. We actually don’t need a Great Leader who believes that He Alone can solve our problems as a society – although that is an appealing solution to a growing, and scary, number of Americans. Rather, we need a society willing to solve its problems as a society.

It’s increasingly clear that we no longer live in such a world. We increasingly live, rather, in neighborhoods where no one disagrees, read news that doesn’t challenge our views, select our own definition of truth like we do our own music, and never have to adjust our preferences to those of anyone else. Neither politics, governments nor countries as we know them will last in such an environment. The question is whether such concepts as common good, or compromise, will.

Care and Concern

At the end of each year, I write a think-piece about the state of the world and where things are headed. This year, I was asked to write a longer disquisition than usual by Aspenia, the Aspen Institute’s European journal.

At the end of each year, I write a think-piece about the state of the world and where things are headed. This year, I was asked to write a longer disquisition than usual by Aspenia, the Aspen Institute’s European journal.

That’s now out and you can read the full version – Welcome to the History of the Future – below, but if you don’t want to plough through all of it, here’s the “Reader’s Digest” version: Despite Francis Fukuyama’s famous pronouncement 30 years ago that we’d reached The End of History, “history is back with a vengeance.” Unlike in the past, “[t]he relevant battles, however, will no longer be those between the public and private sectors, or between one nation-state and another: they will be a contest between the virtual or territorial, cooperative or extractive, consensual or coercive, and connected or chaotic.”

Over the last decade, the economy has slowly transformed into one where “clean” cognitive-based industries have mostly banished “dirty” extractive industries and mechanically-oriented work; traditional gender roles and sexual norms have been overturned; formal apartheid has been crushed; liberal internationalism has been declared the only global social system; and traditional warfare (at least between developed countries) has been largely abandoned. It’s shocking to see all that suddenly falling apart at the very moment of its seemingly-unchallenged ascendancy – only if you don’t notice that that’s pretty much how history works. Liberalism is today’s spent force, while reaction is seemingly in the ascendance.

Nonetheless, the very developments driving this crisis pose serious long-term challenges to the alternatives to open, liberal, democratic societies, as well. The crisis of faith across the world is driven by emergent technologies and their attendant double-edged challenges. These will only accelerate in the next decade or two…. The ultimate resolution will likely produce new forms of government, economics and social organization as different from today’s as our world is from the Middle Ages. No one yet knows what these will look like.

How should we respond to this reactionary moment? As I wrote recently in US News & World Report, I spent a good part of 2017 meeting and talking with opposition figures from such repressive countries: Russia, Turkey, Venezuela. One of them – Andrés Miguel Rondón from Venezuela – wrote an article in The Washington Post, “To beat President Trump, you have to learn to think like his supporters,” that everyone should read. As Andrés forcefully concludes, “Trump’s solutions may be imaginary, but the problems are very real indeed…. Showing concern is the only way to break the rhetorical polarization.” I elaborated on this in How to Stop Creeping Authoritarianism:

I would reframe Andrés’ argument in one respect: It’s not a matter of “showing concern” – like George H.W. Bush’s infamous pronouncement, “Message: I care” – where it’s obvious that it’s simply a message and you don’t. Rather, it’s a matter of actually caring.

Liberals and progressives think that by definition they care; like some sort of GEICO ad, “it’s what they do.” But the prototypical liberal response to the challenges of the changing world – train people for jobs more like yours, tell them to relocate to places like where you live, and end their benighted existence by forcibly imposing on them better values more like your own – is by no stretch “caring.” … Rather, as I noted here a few weeks ago, that’s always been the program imperialists impose on the conquered. Since when have progressives ever thought that morally defensible?

Simply attacking Trump and ridiculing his policies is insufficient. You can say all you want that Trump is lying about bringing back coal and manufacturing jobs – it will have no effect: His voters already know this. People aren’t stupid: They know he’s lying. They like that he cares enough to do so – to pay attention to and respect their concerns, and elevate them to the center of his agenda. That’s certainly more than effete liberals do.

I’m not suggesting fighting disingenuousness with more disingenuousness – I’m suggesting the need for honest concern.

I then offered several economic policy prescriptions with which progressives can start – which you can read in the original – and concluded:

Trump hasn’t done and won’t do anything on any of these fronts — and the GOP certainly won’t, either. Instead of criticizing that — and ridiculing voters for not “getting” it — there’s a better solution: Do something about it.

That is, if, as a so-called progressive, you honestly do care.

One thing you can do is to join in the Greater Good Initiative that I discussed in my last update and help us make a difference.

As always, I welcome your comments below.

Quick Links:

– How to Stop Creeping Authoritarianism

– To beat President Trump, you have to learn to think like his supporters

My pieces last year on:

Welcome to the History of the Future

Eric B. Schnurer

In the past year, the future has come into sharper focus. And it turns out, the future is … history. A quarter century ago, Francis Fukuyama famously wrote that we had reached “The End of History,” with “history” defined as an age-old struggle between repression and freedom, exemplified by liberal democracy, free markets, and human rights. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, both the ideal and reality of freedom had triumphed, and the historic struggle of humanity was completed.

In the past year, the future has come into sharper focus. And it turns out, the future is … history. A quarter century ago, Francis Fukuyama famously wrote that we had reached “The End of History,” with “history” defined as an age-old struggle between repression and freedom, exemplified by liberal democracy, free markets, and human rights. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, both the ideal and reality of freedom had triumphed, and the historic struggle of humanity was completed.

Now, it seems, history is back with a vengeance. The forces of authoritarianism, state-backed economic extraction, and violent intolerance are riding high, both across the globe and in an America that – at least in the Obama years – fancied itself as the liberal paradigm of the future. But the seeds of this seemingly-overnight reversal actually were sown well in advance, and the same, interrelated changes in technology, economics and ideologies mean that the age-old struggle continues. The relevant battles, however, will no longer be those between the public and private sectors, or between one nation-state and another: they will be a contest between the virtual or territorial, cooperative or extractive, consensual or coercive, and connected or chaotic. Welcome to the “history” of the future.

A NEW HOPE (AND CHANGE). Not so long ago, but in a country seemingly far, far away, the United States was a relatively homogenous place. It was not uniform, but it was relatively intermixed economically, socially, and politically (except, of course, in matters of race). Barack Obama’s 2008 election was not so much a departure, however, as the culmination of a large number of long-term demographic, political and economic transformations.

For the better part of a century, the Democratic Party had been the “Party of the People,” representing the interest of working class Americans against the more business-oriented Republicans; it was also a “big tent” party, embracing the disparate interests of conservative Southern whites, prairie populists, urban industrial workers, and, increasingly, racial minorities. (Even the Republicans were somewhat more heterodox than today, encompassing a large number of liberals, particularly on race, as well as far-right fringe elements.) But by a generation ago, Americans were beginning to sort themselves more rigidly by geography, with entire regions and even states largely devoid of one political party or the other. The same was true for such other socioeconomic factors as industrial composition, income distribution, religiosity, and lifestyle, all of which grew highly polarized and segregated by geography. Even while the nation grew remarkably more diverse racially and ethnically, it remained geographically polarized.

By the time of Obama’s election, the Democrats had been remade as a party of coastal, urban, well-educated, multicultural, and well-heeled elites. In contrast, and since Richard Nixon’s day, Republicans had been courting the white working class with appeals to a combination of economic, religious, cultural, and thinly-veiled (if that) racial anxieties. Whatever the emotional appeal, however, this Republican strategy didn’t produce any real support for “anti-government” policies favoring the elite – something Republican leaders didn’t realize until the Donald Trump phenomenon was upon them (and apparently still don’t realize now). The stage was set for both parties to lose their working class base – the Democrats to desertion, the Republicans to a hostile takeover. Moreover, while this analysis focuses on US politics, essentially the same can be said about developments elsewhere.

THE EMPIRES STRIKE BACK. The rising right-wing populism and authoritarian politics worldwide have engendered a continuing debate over whether these are driven by racism and other cultural concerns “or” by economics. In truth, these factors are intertwined.

THE EMPIRES STRIKE BACK. The rising right-wing populism and authoritarian politics worldwide have engendered a continuing debate over whether these are driven by racism and other cultural concerns “or” by economics. In truth, these factors are intertwined.

For nearly two generations, the economy has been moving away from skilled human labor, shifting to cognitive skills at one end of the spectrum and unskilled or, increasingly, non-human labor (a product of the cognitive-skill industries) at the other. Over this period, manufacturing regions have been hollowed out and essentially isolated in country after country – just as agricultural regions were during the Industrial Revolution. Those regions connected to this new cognitive economy have prospered, become more ethnically and culturally diverse, and grown closer together while tearing away from their traditional hinterlands. It is as if the continents had been rearranged – just not physically. Economic inequality between countries has been decreasing. But economic inequality within countries – virtually everywhere – has increased.

And all that was before the Great Recession. The Great Recession was this century’s equivalent of the Napoleonic Wars of the early nineteenth or Great War of the early twentieth – the shattering of the world order. Despite growing inequities, the post-Cold War world still supposed a meritocratic social contract under which those at the top at least cared about, and acted in the interests of, those below. The Great Recession destroyed what faith remained in that social contract: the elites – political, social and economic – not only acted in their own venal interest (both in bringing about the crisis and then in bailing themselves out at everyone else’s expense), but they also demonstrated that, when it came to running the world, they didn’t know what they were doing.

THREATENING DEVELOPMENTS. Not surprisingly, those on the outer fringes of these developments have viewed them as running counter to their interests; they see that those people benefiting from these developments (the elites) and their institutions – political, economic, cultural – decreasingly responsive to their needs. Democratic participation has been falling everywhere for some time, along with faith in government, the media, educational institutions, science, and even the idea of truth itself.

The technological changes underlying these developments are notably bringing radical disintermediation to virtually every industry. This makes the current technological revolution different from those of the past, which were centralizing and hierarchical. (The closest comparison might be the invention of moveable type, which made diffusion of knowledge less costly and more widespread, and eventually led to widespread translation of religious texts into the vulgate, the Protestant Reformation, the attendant birth of the nation-state, and the emergence of modern democracy.) Not only is such across-the-board disintermediating, democratizing, and distributing technology laying waste to industries (from publishing, broadcasting and music to real estate, retailing and finance), it is also necessarily changing the nature of wealth, war, and work – not to mention all forms of authority, including those related to expertise, or truth and meaning. It is erasing lines we have long drawn to make sense of our world, between the physical and ephemeral, ourselves and others, right and wrong, truth and falsehood, here and there.

Of course this is threatening to many. It has engendered a reaction: people are seeking refuge in strong states, territorial bulwarks, traditional values, ethnic demarcations, and even extractive (place-specific, non-virtual, low-cognitive) industries. Vladimir Putin’s kleptocracy, an increasingly-statist China, and the resurgent theocracy of isis have all been held out over the past decade as competitive alternatives, even by many in the West. Authoritarian leaders and parties, riding the wave of working class anger, have seized power and entered government around the world. Trump’s shredding of democratic norms, his administration’s promotion of an ethno-state with impermeable borders, and his abdication of global leadership to Chinese and Russian expansionism, it’s the Indian Summer of empire.

RETURN OF THE JEDI? Serious contradictions abound in this rising global reaction, however. Phillip Bobbitt has observed that “terrorism” in every age is simply the mirror image of the corresponding state structure it opposes. Today, the contending alternatives to the emergent power structures of the twenty-first century all reflect the “New World Order” they ostensibly oppose.

The rebellion against globalism is, in fact, global; the counter-revolution against connectedness is connected. The worldview and underlying economic realities of angry young jihadists, aspiring neo-Soviets, Euro-skeptics, and militant alt-right extremists in the United States are not only all remarkably similar, they are also all quite aware of that. Indeed, they are slowly joining in common cause. The contest thus is hardly between the globally-connected and the parochial – it’s between two emerging global parties.

The “alt” groupings, moreover, are not necessarily politically authoritarian (although they are decidedly anti-liberal and at best apathetic about democracy). Like the radical democratizing and distributed nature of the emerging technologies underlying all this, those who oppose the global direction of recent decades tend toward decentralization and libertarianism as much as the fascism of the past. As has been widely observed, Trump needs his followers more than they need him, and the vast bulk of them seem just as aware as his opponents that he’s a hollow fakir. They don’t empower him for his views, but because he empowers theirs. In many ways, then, the anti-elite movements today – radically democratizing and globally connected groups that reject all leaders and institutions – reflect those very technologies that are shaping the world of the future and against which they are rebelling.

In fact, the strong statists are only hastening the decay of nation-states against which they’re reacting. This is evidenced in the still-simmering subnational revolts in the uk, across Europe, and in both multiethnic democracies and autocracies in the developing world including in Russia and China. Nor is the us immune: “Progressive” states and cities are already increasingly bucking the federal government, both domestically and on the international stage. In this era of discontent, the discontentment hardly stops with the state.

THE FORCE AWAKENS. The European elite has satisfied itself that this post-recession populist nationalism is receding. American liberals similarly console themselves with the belief that Trump cannot possibly win re-election with such abysmal approval ratings (they believe he only won to begin with because of our quirky electoral college system). But this is dubious: Trump’s base is unwavering in its support, while the demographics that most oppose him – the young and minorities – tend not to vote. And there’s an old saying in urban American politics, “You can’t beat someone with no one”; right now the opposition has no one. Not only is there no Democratic contender with the stature, gravitas, appeal and message necessary to improve upon Hillary Clinton’s electoral performance – there is no real Democratic raison d’etre.

THE FORCE AWAKENS. The European elite has satisfied itself that this post-recession populist nationalism is receding. American liberals similarly console themselves with the belief that Trump cannot possibly win re-election with such abysmal approval ratings (they believe he only won to begin with because of our quirky electoral college system). But this is dubious: Trump’s base is unwavering in its support, while the demographics that most oppose him – the young and minorities – tend not to vote. And there’s an old saying in urban American politics, “You can’t beat someone with no one”; right now the opposition has no one. Not only is there no Democratic contender with the stature, gravitas, appeal and message necessary to improve upon Hillary Clinton’s electoral performance – there is no real Democratic raison d’etre.

In part, that’s because the late-twentieth century progressive program has largely triumphed. Over the last decade, the economy has slowly transformed into one where “clean” cognitive-based industries have mostly banished “dirty” extractive industries and mechanically-oriented work; traditional gender roles and sexual norms have been overturned; formal apartheid has been crushed; liberal internationalism has been declared the only global social system; and traditional warfare (at least between developed countries) has been largely abandoned. It’s shocking to see all that suddenly falling apart at the very moment of its seemingly-unchallenged ascendancy – only if you don’t notice that that’s pretty much how history works. Liberalism is today’s spent force, while reaction is seemingly in the ascendance.

Nonetheless, the very developments driving this crisis pose serious long-term challenges to the alternatives to open, liberal, democratic societies, as well. The crisis of faith across the world is driven by emergent technologies and their attendant double-edged challenges. These will only accelerate in the next decade or two. Advances creating new industries and occupations that generate tremendous wealth for many will also render obsolete large swaths of professions beyond the blue-collar jobs that have so far borne the brunt of change. Capital and credit will become easier to obtain and new ventures easier to launch, while the gains from these will be increasingly concentrated in the hands of a limited few who own the algorithms that represent the new capital. The returns on other labor are likely to decline. Ubiquitous distributed technologies will make it easier for anti-liberal forces to penetrate and “hack” connected, open societies, transforming the nature and territory of conflict. At the same time, it will become easier for individuals to undermine oppressive, centralized systems and regimes and to form their own communities of choice.

THE FUTURE OF HISTORY. The ultimate resolution will likely produce new forms of government, economics and social organization as different from today’s as our world is from the Middle Ages. No one yet knows what these will look like. Hopefully – whether virtual or territorial – the cooperative will prevail over the extractive, the consensual over the coercive, and the connected over the chaotic.

What is certain, however, is that history is only just getting going again.

Death and Life

This past weekend was the first Greater Good Gathering – something I hope will become not just an annual event but part of a larger initiative to promote the “greater good” globally. What does this mean? I’ll be discussing that in more detail in several articles and in a future update – but you can already read this coverage of the conference:

This past weekend was the first Greater Good Gathering – something I hope will become not just an annual event but part of a larger initiative to promote the “greater good” globally. What does this mean? I’ll be discussing that in more detail in several articles and in a future update – but you can already read this coverage of the conference:

Greater Good Conference Holds Inaugural Gathering

A Gathering Seeks Levers to Rebuild Common Good

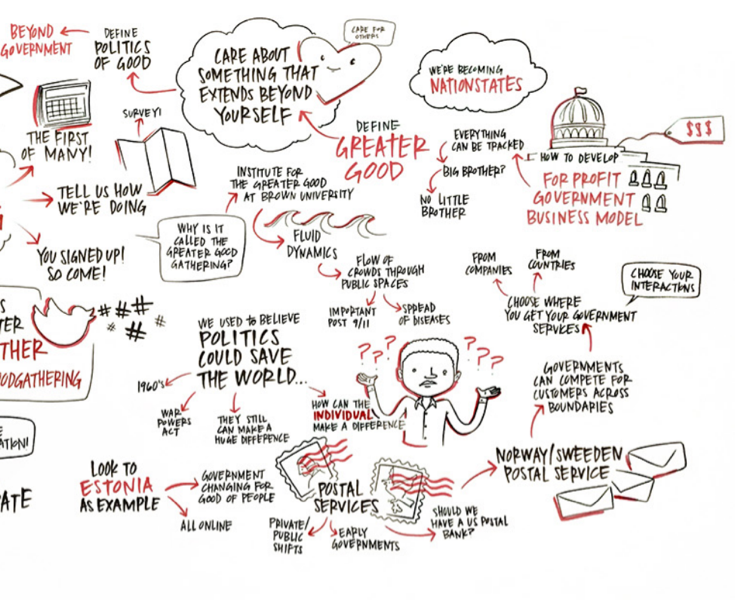

In my own remarks at the conference, I defined my view of “the greater good” as something not partisan or ideological, but rather simply “advancing the good of others than just yourself.” Below is one of the “graphic illustrations” from the conference, summarizing my remarks.

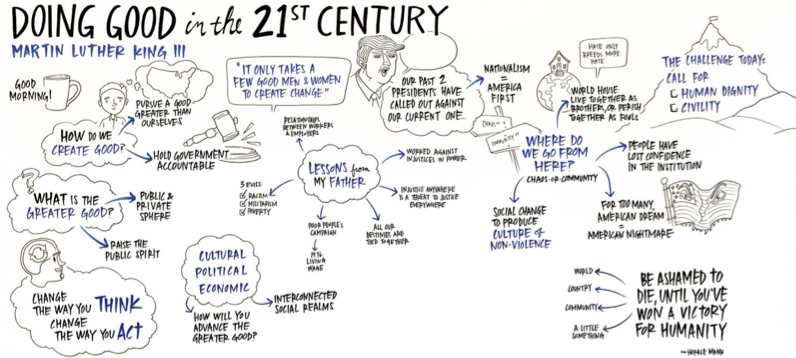

A similar theme was struck by our keynote speaker, Martin Luther King III:

A similar theme was struck by our keynote speaker, Martin Luther King III:

As I discussed in my piece this week for US News & World Report, Live More Life, “For me, this has always been the basis for a particular concern with justice and fairness.” The article relates these “macro” issues to more personal concerns that start from my learning during the conference that one of our cats was dying. “I’ve come to see these passings as less about the awesome finality of death than the wonder of life,” I wrote, which takes us to the heart of this week’s missive:

[W]e can and must make the most of the time we have. The literary critic Harold Bloom, in his interpretation of “The Book of J,” one of the main source documents of what we now know as the Hebrew Bible, focuses on the image of King David.… Despite (if not, indeed, because of) his all-too-human failings – his passion not just for God, but also for conquest, for women, for all around him – David personified an ethos of “more life” that Bloom explicates from all the “J” text as God’s central aim. That doesn’t necessarily mean more years, but it does mean that the purpose of life is to wring as much from those years as possible.

But living life fully cannot possibly mean living life selfishly: To confine one’s concerns to one’s self is to limit oneself even more in time and space than the constraints nature already imposes on us. Why would one do that? In fact, my greatest concern for our country in this time of Donald Trump is not the repugnance that flows from Trump himself, but rather that a near-majority of Americans would embrace an ethos that concerns itself with nothing but the self….

People often shrug at injustice with the words, “Life isn’t fair.” Well, no, it isn’t. But while life itself places conditions upon us, our unique intelligence and moral sense give us the ability to transcend those constraints, to make life, and the world around us, more fair. To do so – not just for ourselves, but even more so for others – is how we, too, pursue “more life.” We ought all weep those times we cannot.

This piece was, in many ways, an unintended bookend to my reaction to the Las Vegas shootings that appeared two weeks ago. As I noted at the very beginning of Change Our Violent Culture, “Las Vegas made one thing clear: No matter the size of the massacre, nothing will lead to gun control legislation in this country.” But, I continued, “frankly, I don’t think we have a violent society because guns are readily available: Rather, guns are readily available because we are a violent society. That’s what really needs to change.” After a discussion of the constitutional and practical impediments to stricter gun laws, I turned to my central argument:

[U]ltimately, combating antisocial behavior, whether words or weapons, is, as conservatives like to assert, a matter of culture more than law…. This goes for everyone: If you’re stockpiling death-dealing weaponry, you’re part of the problem, not the solution. But if you patronize violent movies, buy products that advertise on violent TV shows, let your kids play violent video games, honor singers of violent lyrics, or vote for politicians who cynically promote firearms in bars and schools while banning them (for obvious reasons) from the government buildings where they work, then you’re part of the problem, too.

Because a nation that acted like shooting people is wrong, every day, wouldn’t also experience a mass shooting virtually every day.

I’m heartened that surprisingly large numbers of people seem to see the Greater Good initiative as a ray of hope in an otherwise dark time. Because, as always, where there’s life, there’s hope.

As usual, I welcome your comments below!

Sign up HERE to get my blogs directly to your inbox! Get the latest news and analysis of current events and public policy.

Why I Write What I Write

In the last few weeks, I’ve written several articles on ostensibly different subjects – climate change, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and the collapse of the Republicans’ domestic agenda – that actually share a much deeper underlying unity.

In the last few weeks, I’ve written several articles on ostensibly different subjects – climate change, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and the collapse of the Republicans’ domestic agenda – that actually share a much deeper underlying unity.

Part of that interconnectedness comes from the confluence of so many subjects these days: I learned of Trump’s decision on the Paris accords, for instance, during a meeting on the “Future of Government” – the subject I teach at UChicago – with strategists at European Union headquarters in Brussels, where I was moderating a panel on the US presidential election at a conference on rising populism with many of the international political actors who informed my pieces on French and Russian politics (while also indulging my interest in the Napoleonic Wars that essentially birthed the modern state).

But mainly it’s because, rather than focus on the latest Trump tweet, Russian machination, or implosion of supposed Obamacare “repeal and replace,” I prefer to look for deeper factors and longer-term implications. At least – in a world of millions of journalists, bloggers and Twitter accounts – that’s where I hope I can make a contribution.

At the battlefield of Waterloo, on my recent trip to Brussels, where the fate of Europe was decided 200 years ago.

For instance, this week I tackled The Civil War Over Climate Change. To me, the key development here is not the “climate change” – Trump’s decision has no practical effect unless he’s re-elected in 2020 – it’s the “civil war”:

It’s hardly news that Americans are, metaphorically, living in two separate countries. But the reaction to President Donald Trump’s intention to take the United States out of the Paris climate accord moves us a step closer to making those two separate countries a reality….

Well over 100 of the nation’s mayors, as well as the governors of nine [now twelve] states, have announced that they intend not only to comply with the goals of the Paris agreement – which any jurisdiction (or, for that matter, individual) can do – but also to band together with scores of universities and even private corporations to form a new coalition of “non-national actors,” in the words of Michael Bloomberg, asking the United Nations to be treated on a par with, well, real countries on future climate progress.

This is remarkable both because of its claim to the treatment of subnational governments and businesses as equivalent and on a par with traditional nation-states and for its acceptance of the political break-up of even the strongest nation-state into its squabbling constituent parts. Both represent the future….

Those, of course, have been central themes of mine for the past several years. Trump’s old-fashioned “nationalism” will, in my view, ironically exacerbate the nation’s fraying:

Like similar creeping authoritarians elsewhere, Trump has steadily broadened his definition of “enemies of the people” from, first, ethnic minorities, to elite institutions like the media and court system, to now – mendaciously using the climate issue as his bludgeon – a probable majority of the country who, in Trump’s formulation, by definition (“Pittsburgh, not Paris”) favor foreign interests over America’s.

And meeting at the headquarters of the European Commission (executive branch of the European Union), where the fate of Europe is being decided today.

And that relates to another larger theme I’ve been pursuing: the growing cross-border global realignment, discussed last week in People Are the New Oil (the title comes from a line a Russian politician said to me recently). Drawing on the best-seller, “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty,” by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, the piece focused on the “distinction between extractive and inclusive nations. Economies built on extractive industries – like mining or petroleum – tend not to produce either inclusive economies or inclusive political systems”:

The entire planet is now consumed in a growing economic, political and perhaps military struggle between extractive and inclusive spheres. As I have frequently written here, these spheres essentially overlap with the question whether the societies, economies, communities and individuals concerned are “connected” to the New Economy or not: Those that are connected are booming economically – and also are hotbeds of liberalism and democracy, in the broadest senses of these terms. Those that are not, are not. The distinctions cut across national borders, creating new inter- (and intra-) national fault lines.

The reaction of the reactionaries now running our own country is (at least to pretend) to return to an extractive economy and, like Putin, ignore investing in that more valuable commodity, human capital – to the country’s long-term danger…. [A] new perspective that embraces both the connected future and those left behind by it is sorely lacking and badly needed.

That “new perspective,” called for at the end of both aforementioned pieces, is discussed in Is the Party System Over?. In a recent book, “Once Within Borders: Territories of Power, Wealth, and Belonging since 1500,” Harvard historian Charles S. Maier notes that the distinction undermining our current parties is that between globalists and nationalists (or, Maier calls them, “territorialists”), of which there are both left- and right-wing versions. Uniting all three articles, then, and all three subjects, is this concern:

There’s one glaring gap perpetuating the current systemic instability: While it’s easy to identify globalists generally, and both territorialist Left and Right, there’s so far no “globalist Left” that pays more than mere lip-service to the equity and adaptation concerns of the territorialists. Until that emerges, we’re stuck with the current, crumbling party system.

Quick Links to my three articles:

– The Civil War Over Climate Change

As always, I welcome your comments.

Demagoguery and Democracy

It’s hard to believe we’re only three weeks into the Trump Administration. In that time, I’ve written three articles assessing how we got here and where we’re going; I’ll summarize the thrust here, but I hope you’ll follow the links to the articles and give them a read in the original to get the full argument. (That also helps my “metrics” and keeps my editors happy!)

It’s hard to believe we’re only three weeks into the Trump Administration. In that time, I’ve written three articles assessing how we got here and where we’re going; I’ll summarize the thrust here, but I hope you’ll follow the links to the articles and give them a read in the original to get the full argument. (That also helps my “metrics” and keeps my editors happy!)

On Inauguration Day, I published a piece originating in a conversation a few days earlier with my friend, Jimmy Cauley. Jimmy was the campaign manager for an obscure state legislator in Illinois who was elected to the US Senate in 2004, named Barrack Obama. Jimmy has been saying for a long time a lot of the same things for which J.D. Vance, author of Hillbilly Elegy, has been celebrated in the last year (except Jimmy’s a whole lot funnier). The conversation reminded me of a piece I’d written when Obama was elected president; I’ve raised similar warnings since about Democrats’ failure to address the concerns of white working class Americans. But I was surprised, when I went back and reread my 2008 diatribe, by the Republican response that year that completely foreshadowed the Trump message “by redefining who has been in charge”:

It really hasn’t been George Bush, the largely Republican Congresses, or the 7-2 Republican majority on the Supreme Court – it’s been a national elite of “cosmopolitan” types (you know, highly-educated, diverse, globally mobile)….

Of course, resentment of elites has a long history in America. What has changed, however, is that those who might have felt “bitter” about being left behind by the new economy in prior ages – Jacksonian Era frontiersmen, Southern planters and Western ranchers, underpaid workers in Pennsylvania steel mills or West Virginia coal mines – all voted Democratic, and the Democratic Party was unrepentantly proud to speak for them. Today, the Democratic Party increasingly consists of the well-educated, the worldly, the owners of the keys to the economy of the future – and it is at risk of losing interest in helping those it sees as “bitter,” unfathomably ungrateful, and not just inferior but frightening.

You can read the full discussion in The More Things Change.

Many fear a fascist takeover driven by such demagogic reaction. In Make America Hollow, I argue that “[t]he Americas Bannon and Trump envision are depressing, but not totalitarian: One is illiberal but not necessarily authoritarian, the other authoritarian but not necessarily illiberal. Both lead to a society embodying not so much the banality of evil as the evil of banality.”

Bannon’s conformism is not that of Stalin’s Russia, but of the roughly-contemporary Peyton Place; his vision of America is one – socially, economically, politically, religiously – out of an idealized 1950s…. Matt Bai paints a similarly dispiriting picture in a recent piece asserting that Trump – like other contemporary demagogues – is less Orwell’s 1984, with its “vision of fascist repression,” and more Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, “with [its] trivial, substanceless society.”

Where Trump and Bannon come together “is not the creation of a fascist state, but rather the opposite: The hollowing out of the state as a viable institution.” That, of course, is a subject I write about frequently. Please read the whole piece for more.

Like all demagoguery, much of Trumpism is driven by misrepresentation. Rather predictably, President Trump has chosen a Supreme Court nominee who claims to be guided by the intent of the Framers; as the apparently-rare liberal who actually agrees with conservatives that the Constitution must be “strictly construed” according to “the intent of the Framers,” I’ve got news for them: That doesn’t mean what they think it means.

[T]he Constitution has been amended many times – sometimes in fashions that dramatically changed its meaning. For all intents and purposes, the post-Civil War 14th Amendment represents a new Constitution, fundamentally altering the balance of power between the states and the federal government. It’s debatable that all those 18th-Century guys in white wigs, whom self-described patriots today like to single out, believed in a largely denuded federal government – the motive for many, like Alexander Hamilton, in creating the Constitution was precisely the opposite – but the 19th-Century Framers of the 14th Amendment clearly did not.

You can read the full discussion at A Constitutional Reality Check.

Easy links in this update:

– A Constitutional Reality Check

As always, I welcome your comments below!

A Season of Caring

As the turbulent year 2016 winds down, I’ve bookended the holidays with two pieces about caring. The first, The Age of “Who Cares?”, appeared in US News & World Report two weeks ago and was featured in my last update. The following day, I received an invitation from a Canadian talk show, to discuss it.

You can listen to the whole interview on your computer or smart phone, but here are some highlights:

“Walls are not going to keep the world’s problems out of the United States because the problems are bigger than that and we live in a world that’s largely interconnected now. We don’t have the luxury of not caring about what goes in the Middle East – or any other country, for that matter.”

“At the moment, the focus has clearly shifted to self-centeredness more than a larger vision. And I think that can be destructive to our lives individually and to the society as a whole.”

“I think everybody involved on both sides of this election have paid inadequate due to the needs and problems of other people in this country. It’s not just Aleppo, it’s not just Trump people, it’s not just this election – we’re living at a time of great, great change, and I think it’s leading a lot of people to feel insecure on all sides, and to focus on themselves as a result. And I think that’s understandable. But it’s not good.”

In my new piece for Christmas in US News, So Much You Can Do, I tried to suggest what some responses to these challenges. Please click the link to read the full piece (my editors keep track of that sort of thing!), but here’s the gist:

Instead of crying by the riverbank at the dismantlement of Obamacare, the block-granting of Medicaid, and the defenestration of Social Security and Medicare, or spending the next four years idly proposing a return to similar New Deal and Great Society programs in some imagined future, we can start using [new] technologies to build virtual communities – the real future – that do choose to cross-subsidize health care, secure retirements and educational opportunity for those who need them, and to reap the benefits.

But there are countless other ways on an individual basis to stand against the incoming tide. There are children who need mentoring – and adults who do, too. There are immigrants who need welcoming, and values like free speech that need exercising. There are small acts anyone can undertake every day that make a small difference, but if repeated by the rest of us would make a large difference – in, say, wasting less energy or consuming less needless packaging or paying slightly more to support better working conditions. You can find one way each day to check your self-interest and act with kindness toward another. You could easily fill your day with things that will make a difference in ways that, without you, will go in the opposite direction under the Trump Administration.

You can decry that there’s so little you can do. Or, as you gather with loved ones over this holiday period, and pass by countless strangers in the streets, you can recognize that, in fact, there’s so much more you can do than there is possibly time for.

I’m looking forward to putting a dent in that in 2017. I’ve got in the works:

Our new-and-improved education consulting practice. We recently completed two studies in Alaska, are wrapping up another in Texas, and my whitepaper on school innovations in Massachusetts will be published in the new year.

A new social venture to accomplish some of what’s discussed above. Alumni of the University of Chicago’s business school have volunteered to help work out the financing and technology details, so I hope to “go live” with this venture in late 2017.

Expanded adventures in academia – including a series of forums and podcasts from the University of Chicago on “The Future of …,” flowing from my course there, “The Future of Government”; a new course this winter at Union Theological Seminary in New York on the deeper drivers of right and wrong –from biology to psychology to game theory – and what we can do about them; and a new annual conference tying together all the foregoing at Brown University, to be announced early in the year.

I’ll be giving you details in further updates in the coming weeks. But until then, have a Happy 2017, filled with caring!

Happy holidays from our family to yours.

Charles Adler Tonight

My piece in US News & World Report last week, The Age of “Who Cares?”, attracted the attention of a Canadian talk show, Charles Adler Tonight, which invited me on to discuss the article. In the course of a 15-minute interview, I talked with host Charles Adler about Syria, Donald Trump, racial animosity, international responsibility, and how they’re all interrelated:

“We’re quite fortunate in the US, and we’re quite fortunate in most of the western world, compared to huge swaths of humanity today. It’s just, things aren’t quite as good in a lot of ways as most of us would like it to be, and they’re certainly nowhere near as good for a large segment of the population in this country as they could be and should. I think they rightly feel that a lot of people don’t care about their problems, and it’s hard to get exercised about other people’s problems in that kind of environment.”

You can listen to the whole interview on your computer or smart phone.

Thanks, but No Thanks

In the two weeks since Election Day, I’ve been trying to explain to various audiences what I think it all meant. Just before the polls closed that evening, I moderated a panel of experts from a half-dozen countries on what the election would mean for the rest of the world. As I discuss in a piece out today in US News & World Report, “The New Old Nationalism,” the Russian pollster on the panel

In the two weeks since Election Day, I’ve been trying to explain to various audiences what I think it all meant. Just before the polls closed that evening, I moderated a panel of experts from a half-dozen countries on what the election would mean for the rest of the world. As I discuss in a piece out today in US News & World Report, “The New Old Nationalism,” the Russian pollster on the panel

made an interesting comment to me in advance of our session: Russian citizens have more sympathy to Trump, he said, because he is an “American nationalist, not globalist.” Not that long ago, “an America nationalist” would have been a damning epithet coming from the Kremlin, basically a longer version of the word “imperialist.” Now, it’s … something that both foreigners and “conservative” Americans alike embrace[:] They see global economic and social integration as … a perversion of the rightful natural order, in which different peoples hold discreet territories, separated by walls.

… All of this – the tribalism, the illiberalism, the eternal struggle – its proponents would say, is simple realism. It is, in any event, the “alt” view of the future that the 2016 elections (and those coming in 2017) are elevating to global policy. I believe that, in the long-run, it’s a view that will lose. But in the long-run, we’re all dead.

One of my greatest regrets about 2016 is an article I didn’t write: When I returned from a European conference in May at which the dynamic duo of Kristina Wilfore and Stephanie Berger presented polling data on attitudes toward women, I began to write a piece predicting that misogyny would become the central fact of this campaign. My editors persuaded me to split the resulting diatribe into two parts, one of which became the first of several I’d write on how Hillary Clinton needed to overcome some of this by addressing the concerns of white working class men – but the argument on the coming wave of misogyny got sidelined, at least during the campaign. After the piece I wrote a few weeks ago complaining that discussions of “morality” have been largely hijacked by the subject of “sex,” the folks at Aspenia asked me to expand the argument for an issue on “Women & Power”; an abridged version was published online yesterday in Italian – until the English version is published, you’ll have to make do with this synopsis, building off Newt Gingrich’s outburst late in the campaign to Megyn Kelly: “You are fascinated with sex, and you don’t care about public policy”:

But the description – fascinated with sex, don’t care about public policy – might best fit the American public as a whole. One major subtext of the 2016 election has been sex and America’s ambivalent relationship with it…. Issues involving women and power – whether political leadership, their broader place in society, or their preponderance on the receiving end of all forms of violence from the physical to economic exploitation and poverty – aren’t really about whether they are strong or intelligent or emotionally stable enough to lead others or to protect themselves. They are, rather, about women’s position as gatekeepers of men’s access to the reproductive process – and sex – and men’s desire to wrest away that control for themselves.

In case all this leaves you unduly depressed headed into Thanksgiving – at least, any more so than most people I know already are – I argued in my main assessment of the election itself that you shouldn’t be, although not perhaps for the reasons most people might think:

Yes, there are some authoritarian, reactionary people amongst both Trump’s supporters and his advisers – but that’s not the majority, amongst either them or the rest of the American public. So put on your big-boy pants….

The future belongs to the decline of the nation-state. That sounds just as scary to liberals as it does to the reactionary, anti-globalist “nationalists” of Trumpworld. The real challenge for progressives is whether greater equity can be created within, not ignoring, this reality. Trump’s victory ironically provides the opportunity to explore the possibilities today rather than, as would otherwise be the case, sometime later this century in (as I described here just before Election Day) an even more troubled environment.

You can read the full piece, “Party Will Be Irrelevant,” here. As always, I welcome your comments. Meanwhile, a Happy Thanksgiving to all!

It’s a Tie!

Which will it be?

Which will it be?

Veterans of campaign work know that the slowest day of the year is, ironically, Election Day with its long wait for the results. For those of you counting the hours to poll closure, standing at a polling place waiting for voters to show up, or simply trying to find someone with exit-poll results or the latest turn-out rumors, here’s some reading material to while away the time. My last pre-election piece ran Friday in US News, and, in it, I pulled together my thinking over the past year on the future of government, the Trump phenomenon, Brexit, my visits to six countries and meeting political leaders from several more, and evolving technologies. If you want to know what happens starting tonight when the polls close, here’s my best guess:

Looking back at the turn of the 22nd century, the collapse of the nation-state system, which had existed for roughly 400 years, now seems obvious and long-overdue. But historians agree that the critical point, when the outcome went from unimaginable to unstoppable, was the disputed United State election of 2016, which ignited what has come to be known as the “Disunited States” Period.

Rumblings had been coming for decades: The collapse of empires throughout the 20th century. The increasing frequency and severity of global financial crises. The rise of nonstate challengers to the major states. And the geometric growth of technologies that simultaneously undermined the two defining elements of the “modern” nation-state – control over (1) the monopoly of force, and (2) a defined geographic territory.

Together, these changes had opened up a wide cleavage between two broad classes globally, cutting across traditional national borders: the so-called “Globopolitans” – sometimes denounced in the ensuing wars as the “elites,” but really people of all economic backgrounds in the interconnected global metropolitan centers, where incomes generally were rising – and “Remnants” of the less globally integrated regions of every continent, whether within single countries (like the interior of the former United States) or across multiple countries (like the Middle East or Horn of Africa). Differences in income levels between countries had narrowed – but incomes within them severely diverged worldwide. Globopolitans, regardless of location, saw a world of opportunity growing ever wealthier and more equitable; the Remnants saw a world of stagnation, widening unfairness and, perhaps as importantly, “cultural extermination” due to post-modern global change.

Remnants believed their salvation lay in eradication of this globalist threat through a return to earlier cultural, economic and national structures. They failed to recognize, at least initially, the twin ironies of their anti-globalist grievances: This actually connected them with similarly aggrieved peoples globally – the gods they worshiped and cultures they defended may have differed, but the worldviews were much the same. And it triggered the ultimate destruction of the traditional “nations” on which their traditionalist ideological agenda became increasingly fixated.

Working class revolt, fueling populist politics of both left- and right-wing varieties, simmered across Europe and other regions to a lesser extent in the wake of the global financial crisis that struck in 2008, but the first clear flare was the surprise “Brexit” vote in Britain to leave the European Union in mid-2016. This was hailed as the triumph of traditionalist, nationalist values over a condescending globalist elite – but it led in quick succession to the break-up of first the United Kingdom, then of England itself: Globopolitan London jettisoned the anti-globalist regions holding it back, pegged its currency to the American dollar and reunited informally with Scotland, Wales and Ireland to rejoin the European economy. In many ways, this presaged the (typically) larger and more violent developments in America.

The 2016 U.S. presidential election was widely perceived to be the nastiest in well over a century, with underlying themes of fraying racial, sexual, religious and national identity. But most historians today ascribe the uprising, and ensuing crack-up, to the tectonic economic forces described above.

The actual winner of that election was lost to the historical record in the disorder that followed. But we do know that the results were so close that they triggered months of unrest, refusal to accept defeat by the losing side and bitter paralysis of the government. In a notable departure from the country’s long-standing norms, both presidential contenders were subjected to post-election prosecution and ended up jailed. A deep, worldwide recession resulted, exacerbating the underlying tensions even further.

If you want to know what “happened” after that … click here to read the rest of the piece. Whatever you do, exercise your right as an American: Get out and vote! And as for the results, register your prediction below: Which tie will I being wearing on Wednesday?