Politics

Truth – and Consequences

The vast majority of Americans appear to have re-learned the long-standing political dictum, “Elections have consequences.” Voters turned out in record numbers for last month’s mid-term elections – not just those determined to send a message of “resistance” to President Donald Trump, but also those signaling their support. The run-up to and aftermath of these elections offered numerous opportunities for commentary online, in print, live, and on TV. So, in this update I’m providing a (multimedia!) synthesis:

The vast majority of Americans appear to have re-learned the long-standing political dictum, “Elections have consequences.” Voters turned out in record numbers for last month’s mid-term elections – not just those determined to send a message of “resistance” to President Donald Trump, but also those signaling their support. The run-up to and aftermath of these elections offered numerous opportunities for commentary online, in print, live, and on TV. So, in this update I’m providing a (multimedia!) synthesis:

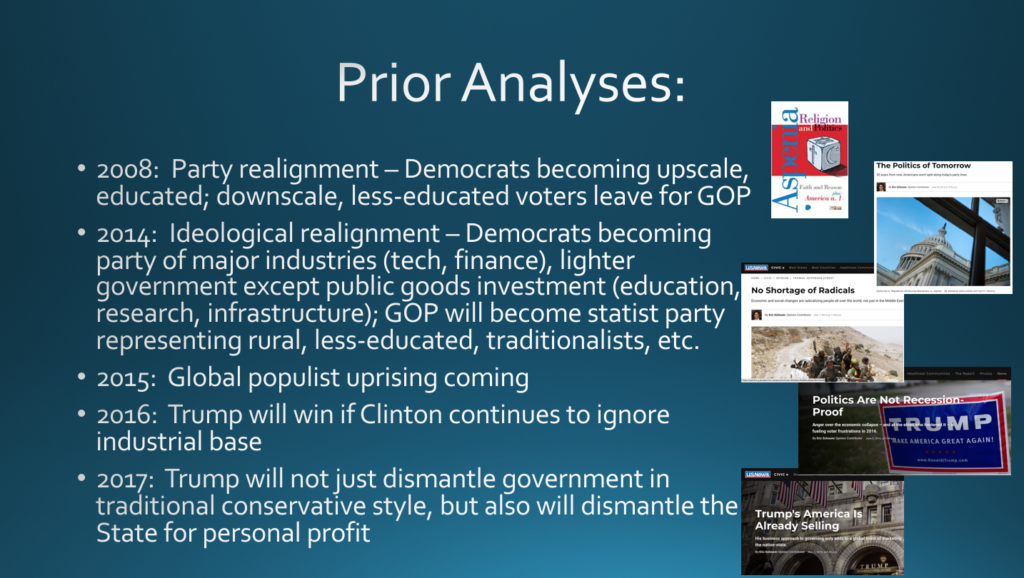

The country is divided between those who benefit from the global, digital economy, and those who don’t.

The Rome, Italy, branch of the Aspen Institute unveiled its new-and-improved website the day before the election, and its launch prominently featured my piece, Two Americas and the lost center, which concluded:

The Rome, Italy, branch of the Aspen Institute unveiled its new-and-improved website the day before the election, and its launch prominently featured my piece, Two Americas and the lost center, which concluded:

One of these two nations clearly was winning the economic, cultural and political wars until recently; the other has predictably struck back with a vengeance. Both now believe, probably correctly, that they are in an existential struggle with the other where only one will survive.

There are, in short, two sides – but no center.

Democrats and progressives should be – but are not effectively – addressing the concerns of those left behind in this economy.

The weekend before the election, I was visited at my home by Bruce Hawker, a correspondent and producer for Australian TV traveling the US in the weeks leading up to the midterm election.

We’ll have to wait until early 2019, when Bruce’s documentary airs in Australia, to see exactly what I said (even I don’t recall). But I spoke on the same general theme a few days earlier at the University of Scranton, where I explained, in response to one question, my concern with progressives’ failure to address the economic anxieties of Trump voters. (As a bonus, here’s my 3-minute explanation of blockchain.)

Disaffected and economically disfranchised Americans have risen in revolt and seized political power on behalf of an illiberal and undemocratic ideology.

I wrote this piece for Aspenia Online, All Globalists Now, just after the election in response to President Trump’s closing theme framing the country’s choice as one between “nationalism” and “globalism”:

In sum, the supposedly-nationalist and anti-globalist movement is in fact global in scope and and transnational in organization. The foreign regimes that serve as its models and allies are the most violative of any today of the sovereignty and internal integrity of others. Their national cheerleaders, however, welcome these international models not only to guide but also, if necessary, to override US institutions in constructing a similar “nationalism”.

In sum, the supposedly-nationalist and anti-globalist movement is in fact global in scope and and transnational in organization. The foreign regimes that serve as its models and allies are the most violative of any today of the sovereignty and internal integrity of others. Their national cheerleaders, however, welcome these international models not only to guide but also, if necessary, to override US institutions in constructing a similar “nationalism”.

The print version of Aspenia is republishing this month my piece, Urbi et Orbi – previously published only in Italian – which similarly observes:

The tripartite division between producers, transformers and predators described above generated the same dynamic that we see in today’s populism, with the left trying to appeal to an urban middle class against an economically and politically predatory elite, with the conservative wing of that elite appealing, usually more successfully, to the producers in the exurban extractive economy by attacking the allegedly-parasitical professional classes.

The tripartite division between producers, transformers and predators described above generated the same dynamic that we see in today’s populism, with the left trying to appeal to an urban middle class against an economically and politically predatory elite, with the conservative wing of that elite appealing, usually more successfully, to the producers in the exurban extractive economy by attacking the allegedly-parasitical professional classes.

Not surprisingly, this illiberal, anti-democratic movement is gaining and holding power by suppressing the exercise of democracy. My CNN debut came in this piece critiquing the Republicans’ increasing reliance on voter suppression as a means of holding onto power:

As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg trenchantly observed in her dissent, however, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” It’s now also clear, to continue Ginsburg’s metaphor, that putting your umbrella away when it’s not raining, as Roberts would have it, is usually sufficient itself to provoke a cloudburst.

The majority of Americans, who are basically doing well, reject this ideology. History is on their side – but the country’s future could still go either way.

In The Wave Election, to be published by Aspenia later this month, I argue that “there is a slow-moving tide of history of which today’s events are merely a part – perhaps a frothing bubble, perhaps a cresting whitecap, on a larger, longer, slowly rolling wave.” The piece concludes with this warning:

The Trump phenomenon represents a powerful undertow running counter to the tide of history – a xenophobic reaction to an America moving in a more socially-liberal, more technology-centered, more globally-integrated and multicultural direction. That tide will keep rolling in, on larger and larger waves. But the undertow is always there, and can be deadly if you don’t pay it proper respect.

In the short term, I still give Trump a slightly better than 50-50 shot at re-election.

The day before the election, I moderated a panel of international experts in DC – as I had two years ago – to discuss what our election meant to others around the world. Virtually none of the foreign visitors in attendance expected Trump to be re-elected – while I did.

What do you think? As always, I look forward to your comments below.

And please check out the second annual Greater Good Gathering that I’m organizing in February in conjunction with Columbia University, Union Theological Seminary, and the American Academy of Political Science. Focusing on the ways that technology today can threaten a shared sense of “community” and the common good – or fulfill its original promise to help build them – the conference will feature tech executives, prominent journalists, leading academics on all aspects of the tech revolution from dating apps to cyber war, and top officials from the Bush, Obama and Trump Administrations. Register today, and spread the word!

Here It Is

I’ve been promising for several months to give you the details of the idea I’ve been working on the last three years – the business model for what’s going to replace government as we’ve known it for at least the last 2,500 years. Sorry that’s taken me so long … but: Here it is!

I’ve been promising for several months to give you the details of the idea I’ve been working on the last three years – the business model for what’s going to replace government as we’ve known it for at least the last 2,500 years. Sorry that’s taken me so long … but: Here it is!

As I discussed previously, the origins of this idea lay in what I’ve been writing and teaching the last several years about “The Future of Government”: that modern technologies like the Internet, the platform business model, and blockchain, by moving us increasingly into a virtual world where distance, mass and geography matter less and less, are undermining the traditional national state. The question then becomes what replaces nation-states – an issue at the heart of the current worldwide political struggles between globalists and nationalists – and, in particular, What happens to so-called “public goods”?

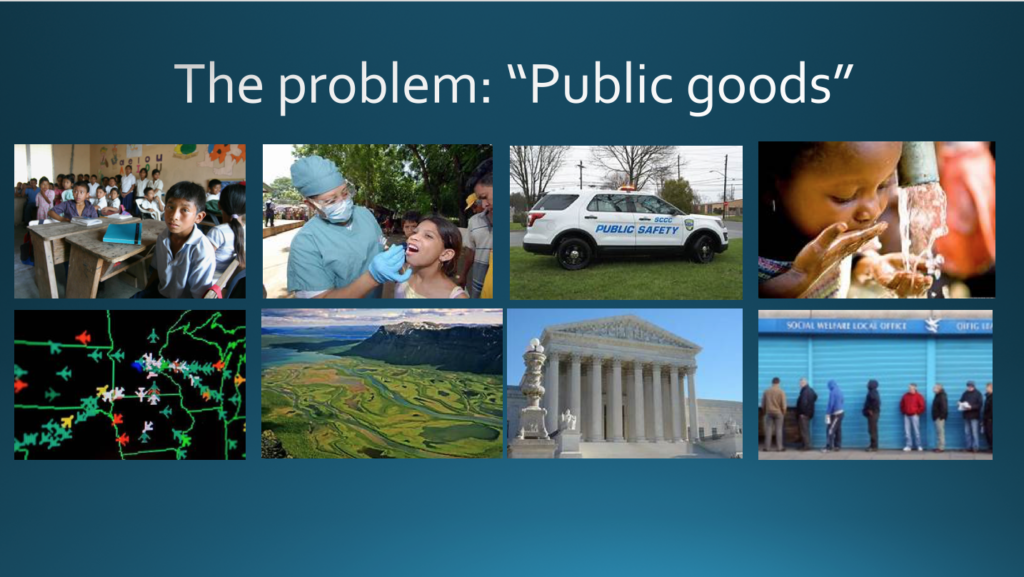

In economic jargon, “public goods” are non-rivalrous and non-excludable – in other words, my consumption doesn’t deplete the amount available for you, and I can’t “own” it and keep you from using it. Public goods include much that we’ve come to expect governments to provide, such as public safety, public health, social insurance, education – things that create broader benefits for society as a whole, and from which everyone benefits. “Public goods” thus ultimately form the rationale for government itself. What happens to them in a society where technology increasingly allows resources to escape the territorial clutches of governments more easily than ever, and allows us all to opt-out of obligations we don’t want?

I think they die – unless we can develop a method to capture (or “monetize”) their benefits and share them back to all (and only those) who choose to subsidize them. In other words, we need a profit-making model for public goods. Fortunately, the same technologies weakening nation-states today make possible the formation of voluntary, virtual communities.

I think they die – unless we can develop a method to capture (or “monetize”) their benefits and share them back to all (and only those) who choose to subsidize them. In other words, we need a profit-making model for public goods. Fortunately, the same technologies weakening nation-states today make possible the formation of voluntary, virtual communities.

Investments in “human capital” – education, health care, child development, social insurance – aren’t just liberal, feel-good things: They pay measureable economic “dividends.” For example, the average lifetime earnings of an African-American single mother go up by a half-million dollars if she has five-years of day care for her kids. A child’s lifetime income goes up by $6,000 (in present value) for every year that child has a good, instead of simply a mediocre, classroom teacher. These returns not only pay for the social investment – they’d turn a healthy profit for anyone financing them in place of the government.

Closing the Circle

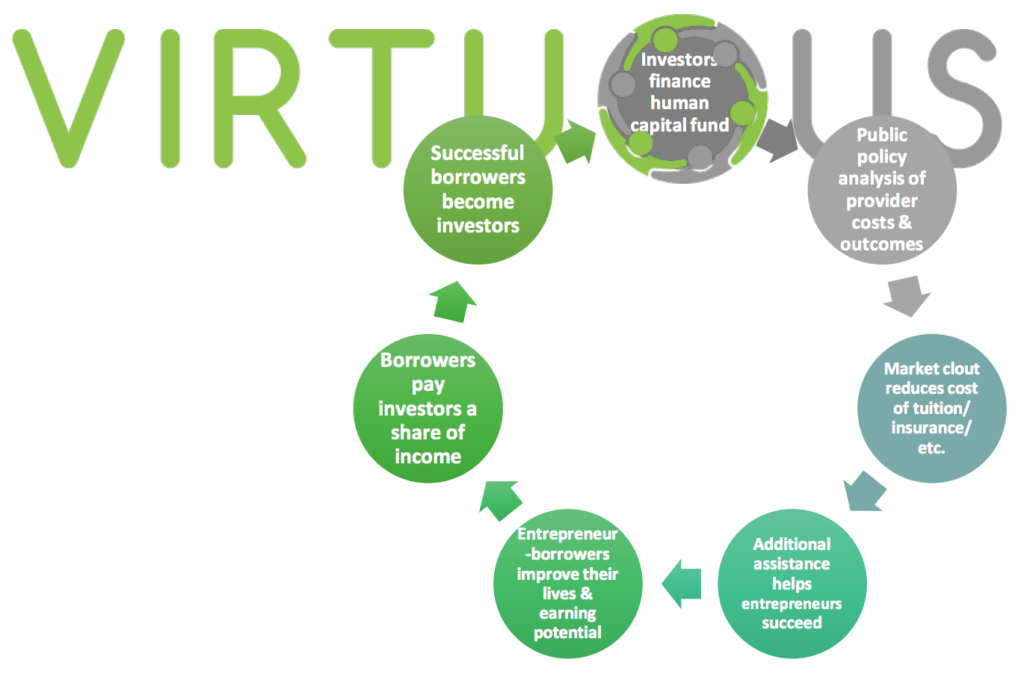

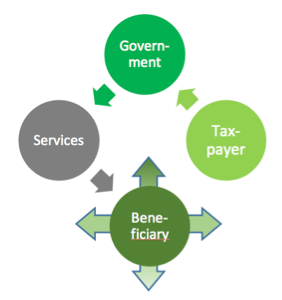

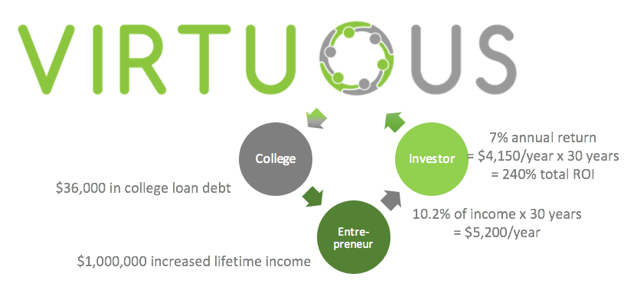

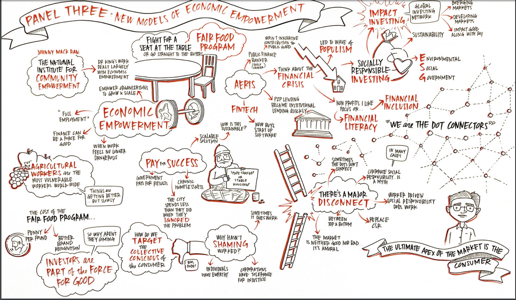

This is easiest to see in the commonly-understood example of return on higher education. Above are two illustrations I frequently use: The way things are today, taxpayers pay for government-provided services that (hopefully) improve people’s lives – but the benefits don’t necessarily accrue observably to the taxpayer. But if we treat beneficiaries as entrepreneurs, in whom we make an investment and then reap a percentage of the “profits,” the increased income alone would pay a healthy rate of return.

Such “income share agreements” already exist in higher ed; my new business, Virtu.us, aims not only to expand their presence but also to bring this concept to financing job training, high-quality child care, various forms of social insurance, and even provision of the kind of K-12 schools every child needs and deserves. All through an easy-to-use app and web portal.

But the concept doesn’t stop there. As the graphic at top illustrates, this model will incorporate policy analysis insights as to “what works” into market assessments of how best to invest in individuals; use the market clout of a growing community-of-interest to drive down the price of these services for everyone; and even expand over time into a wider potential range of “public goods” encompassing, well, virtually all current government activities. Eventually, this becomes a fully-fledged, on-line community – providing the things people want, but decreasingly find today, in real-life communities, let alone the on-line kind.

Perhaps you think the idea of private “governments” is terrible. Perhaps it is – but as public institutions as we know them decay, a new alternative will be needed for a very different future. Perhaps you think everything going on today will pass in another two years (or two weeks); perhaps it will – but the economic, political and technological phenomena driving public disinvestment have been going on for the last 40 years, and are occurring today everywhere across the globe. As you know if you’ve been following what I write for the last, oh, decade or so, the need for a new model of public-goods investment – and social progress – isn’t a passing Trump phenomenon: It’s the defining political challenge of our time. Virtu.us is my attempt at an answer.

Perhaps you think the idea of private “governments” is terrible. Perhaps it is – but as public institutions as we know them decay, a new alternative will be needed for a very different future. Perhaps you think everything going on today will pass in another two years (or two weeks); perhaps it will – but the economic, political and technological phenomena driving public disinvestment have been going on for the last 40 years, and are occurring today everywhere across the globe. As you know if you’ve been following what I write for the last, oh, decade or so, the need for a new model of public-goods investment – and social progress – isn’t a passing Trump phenomenon: It’s the defining political challenge of our time. Virtu.us is my attempt at an answer.

If you want to know more, there’s a 60-page white paper online at ericschnurer.com/virtuous: Please read it – I really want your comments and feedback! If you’d like to do more, let me know: We need programmers and project managers, futurists and finance whizzes, analysts and actuaries, marketers and MBAs. One way or another … we need you!

Quick Links:

Also, the last issue left out the link to my recent article about the collapse of the center: http://www.aspeninstitute.it/aspenia-online/article/two-americas-and-lost-center.

Coming next:

An analysis of the 2016 midterms

The role of policy in campaigns

How we helped to strengthen one of the poorest school systems in America

Takeaways from my new course at Brown University on poverty and the future

Again, I welcome your thoughts in the comments below!

Speak of the Devil

In the past several weeks, I’ve had an unusual number of opportunities to speak to various groups about things I’m working on – and in the next few months I’ll be speaking and teaching at universities and conferences from Providence, Rhode Island, to Nairobi, Kenya. And, of course, I hope to welcome all of you to the second Greater Good Gathering, in New York City this November.

In the past several weeks, I’ve had an unusual number of opportunities to speak to various groups about things I’m working on – and in the next few months I’ll be speaking and teaching at universities and conferences from Providence, Rhode Island, to Nairobi, Kenya. And, of course, I hope to welcome all of you to the second Greater Good Gathering, in New York City this November.

But today I want to share with you the talk I gave at the recent Impact Summit in New York City, a three-day conference for computer science students from all over the country interested in social good. Following a 24-hour “blockchain hackathon,” and discussions on blockchain and artificial intelligence, I was the last to speak on a panel the last day on “The Future of Democracy.” I’ve got to warn you: When I finished, the moderator – a college contemporary – reacted that my presentation was “interesting” but “scary.”

This is a reaction I hear frequently from my peers – but not younger Americans. People often say they find my predictions “scary” or “depressing” because I talk about things we take for granted and care about – like countries and democracy – changing dramatically in just the next few decades. But I don’t think that’s scary or depressing – just different. The world is very different today from, say, the Middle Ages, and if you told people then about the radical changes coming – in religion, government, social structure, commerce – they probably would’ve called it “scary” and “depressing,” too … but I don’t think any of us would want to go back. We have no choice but to move forward – our choice is what we do with that. And no-one knows that better than today’s young people.

In fact, I asked the students, “Do any of you find this ‘scary’?” None raised their hands. “Of course not,” I concluded to general laughter, “because you already know this is what’s coming.” I had opened (again to general laughter) with a piece I wrote two years ago:

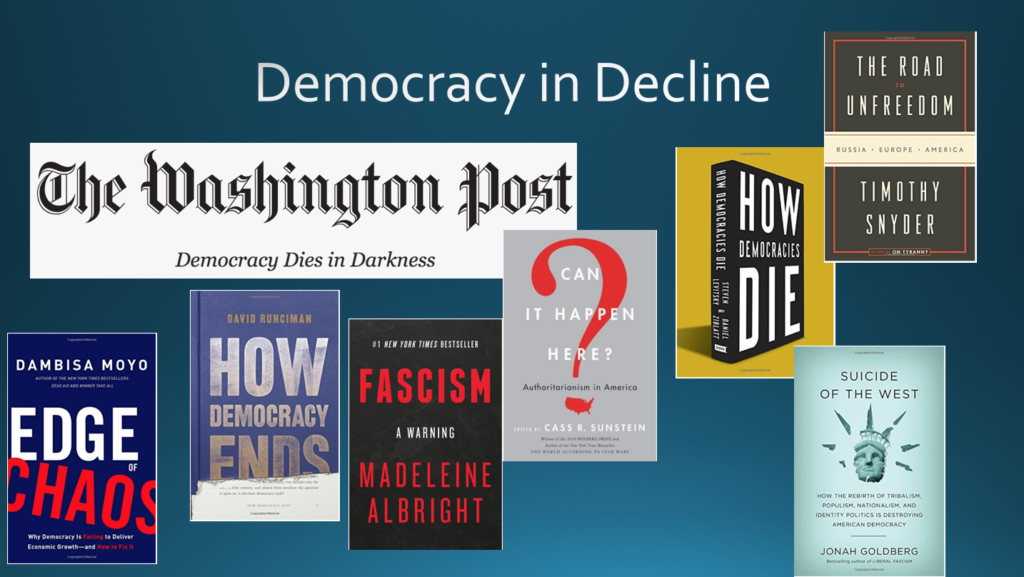

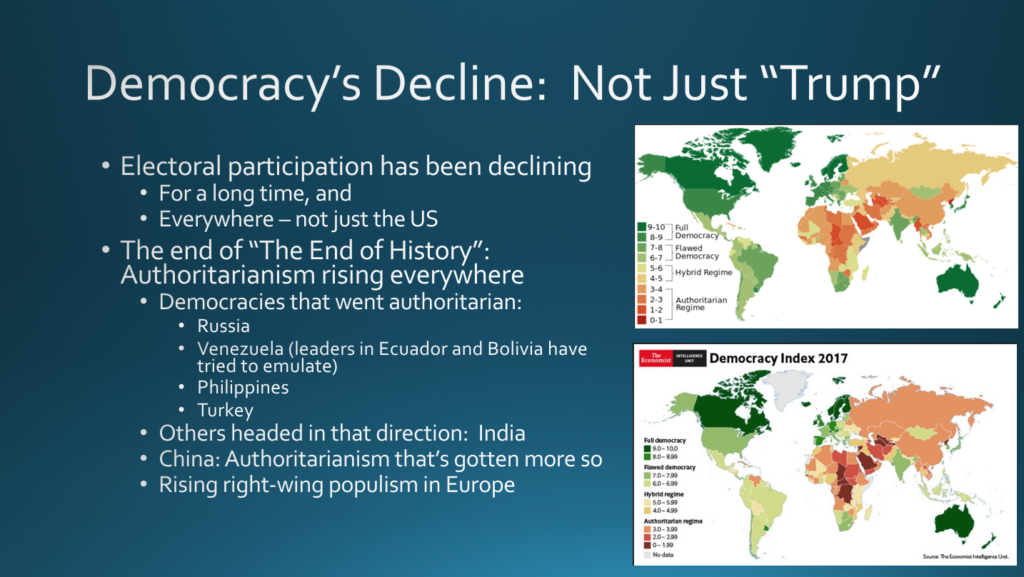

Pessimism about democracy is widespread today – largely because of President Trump – but democracy has actually been declining worldwide for the last two decades, for a wide range of reasons, basically spurred by technologically-driven changes in the economy:

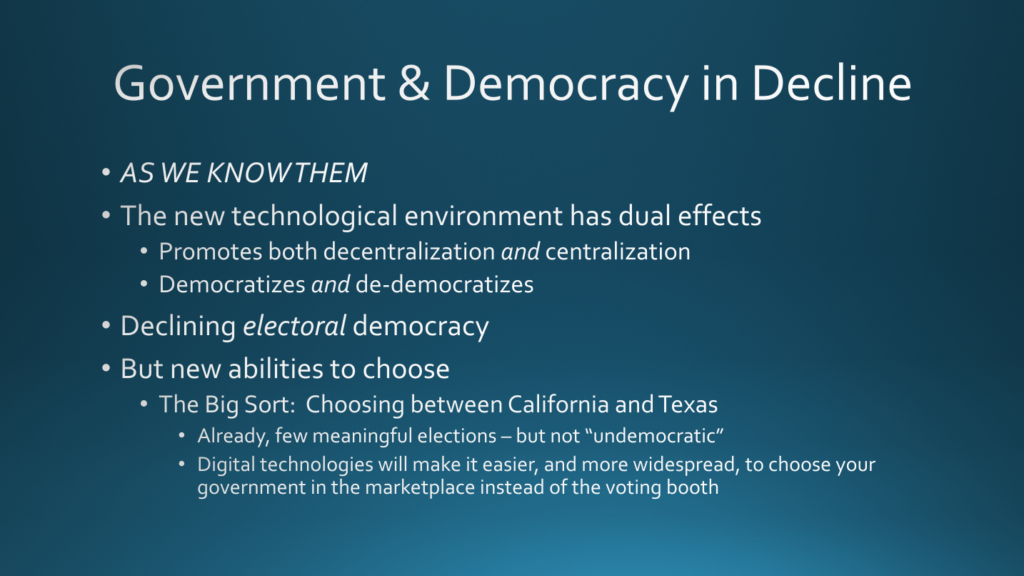

As I’ve been saying for a while, countries as we know them (or, more precisely, “nation-states”) are being undermined by this technological change, just like “business models” in other fields of human activity from music and publishing to manufacturing, transportation, and lodging.

We really shouldn’t be surprised, then, that governments and democracies are – like these other models – in eclipse … as we know them. Democracy – by which we mean political, particularly representative, democracy – is in dangerous decline and under competitive threat.

But the world is also being radically democratized in other ways, providing a wide range of choices thanks to technologies – particularly blockchain – that will go much further than currently imagined to disrupt the world we know and provide us with new bases for forming communities and governments. This is already happening – e.g., in Estonia, which has put all its government services online through blockchain and started making them available for people anywhere in the world:

As this becomes more and more common, the line between “public sector” and “private sector” will blur and disappear – in fact, it’s already doing so:

Businesses are increasingly competing against governments to provide, essentially, “governmental” services – including adjudication, regulation, enforcement, security, intelligence, and waging war. Some of these aren’t even so new. But here’s the problem: Some services governments traditionally provide – “public goods” like education, public health, justice and public safety – are at risk of disappearing, for a simple reason: They don’t make money. As technology provides citizens with greater ability to “opt-out” and choose alternatives, public goods are becoming harder to fund because, by definition, they can’t exist in a world where people opt-out. Until now.

Fortunately, technologies like blockchain will allows us to create new models making it easier to:

• aggregate people;

• agree on and enforce rules;

• monetize, capture, and redistribute the gains; and

• exclude “free-riders” who don’t play by the rules…

… all the things we created government for. And it’s that – not “coins” or “registries” – that represents the true promise of blockchain. So, I’ve been developing a whole new “operating system” for the age-old technology called “government.”

It will deliver what we want from “governments” and “communities” – but decreasingly find today in either the public or private sectors: Enabling people to invest in each other’s futures – through things like educational opportunity, job training, day care and family supports, and affordable insurance against health care costs and life’s other vicissitudes. Creating parks and public places. Providing security and privacy for both people and their data and identities. Using collective action and market clout to protect consumers and to lower costs, and even drive pay-for-performance in service delivery and other “public policy” improvement. We call this new “government biz”:

And we’re going to want you to get involved.

And we’re going to want you to get involved.

I’ll tell you how in my next update.

As always, I welcome your thoughts in the comments below.

The Beginning & The End

Out in New Mexico recently, I was able to mix kayaking over Class 3 rapids, hiking at Tent Rocks National Monument, and eating at celebrated restaurants, with catching up with old friends – like former Governor Bill Richardson. In between, I spent some time at Santa Fe’s first-class museums.

Out in New Mexico recently, I was able to mix kayaking over Class 3 rapids, hiking at Tent Rocks National Monument, and eating at celebrated restaurants, with catching up with old friends – like former Governor Bill Richardson. In between, I spent some time at Santa Fe’s first-class museums.

One of these, the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, covered economic and cultural changes over a millennium ago along the Mogollon Rim – a sharp drop-off between high and low deserts that stretches across almost all of Arizona and New Mexico, where I spent a lot of my youth. The original “basket-weaver” culture above the Rim is so-called because it knew no pottery. But eventually, the superior technology of pottery-making filtered its way in from elsewhere. So did the bow, whose superior firepower provided a more convenient means of defense than retreating each night atop the Rim, enabling villages to relocate down the steep escarpment to the valley below, where their crops grew. Here, in an ancient world far different from our own, communities were being uprooted, and perhaps for the unfortunate basket-weavers their source of livelihood destroyed, by “transborder” flows of new technologies and ideas.

Similar historical developments have been on my mind lately. My friends at the European branch of the Aspen Institute recently asked me to write on two seemingly-different subjects – the Trump Administration’s relationship with business, and the future of cities. But understanding where we are today, and where we’re heading, requires seeing these as merely the latest incarnation of tensions going back to the dawn of humanity.

My forthcoming piece for the journal Aspenia, entitled Urbi et Orbi (“To the City and the World,” the Pope’s traditional greeting), takes a roughly 60,000-year tour of the “[t]ension between nomadic, hunter-gatherer, and even pastoralist lifestyles, on the one hand and sedentism,” on the other. With a quick recap of the Cain and Abel story – about which I’ve written before as a parable of economic and political change not unlike today – the piece summarizes the intertwined emergence of both city and state as sources of increased sophistication and change, but also increased inequality and economic exploitation. Noting that “perhaps the most exploitive social and economic relations were always those between cities and the more traditional agricultural communities in their hinterlands,” the piece turns to an extended comparison between the food chains found in the natural world (drawn from my readings for Deep Policy discussed in the last update) and those in human societies:

The tripartite division between producers, transformers and predators described above generated the same dynamic that we see in today’s populism…. There is thus nothing new in today’s global clash between a largely urban, cosmopolitan, socially liberal society based on a transnational New Economy and a largely exurban, place-oriented, traditionalist society rooted in an increasingly-secondary or tertiary extractive economy.

My other recent article, Trump’s traditional Republican economic choices, argues that, despite the initial horror of the business elite and GOP establishment, they have all largely made their peace with Donald Trump – because his policies are really “perfectly consistent with what Republicanism, and to a lesser extent ‘conservatism,’ have long become.” These policies are instead – predictably – squeezing the very voters who supported and continue to support Trump and Republicans. As Urbi et Orbi shows, the same factors have played out historically in every polity since Ancient Greece.

I’m often asked by people on the Left why they should care about these benighted voters. The first answer is that peoples whose cultures and livelihoods (regardless of whether you share them) are threatened by change – whether the advent of pottery or the Internet – are precisely those about whom the Left ought to care.

The second is that, “The tragedy of the moment is that Trump’s opponents are offering very little to those on the short end of the stick from these developments, who are right to be angry – while Trump’s appeal to them is based purely on selfishness, not on what is best for the country as a whole. Unfortunately, the same can be said of the entire thrust of Trumponomics.” The piece concludes:

The symbiosis of government and business into one big rent-seeking enterprise is precisely what principled conservatism has opposed for decades, and criticized in modern liberalism…. Candidate Trump explicitly campaigned against just this – and yet, as both a private individual and as President, Donald Trump literally personifies it. In Trump’s America, more so than ever before, government itself is up for sale. This represents perhaps the logical end-point of the short-term, self-serving ideologies that passed for “conservatism” or “pro-business” in recent decades – but it also has represented the end-point of democratic and capitalist decline throughout history.

With former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson

As always, I welcome your comments below.

Hack This Planet

I recently taught a new course – “Deep Policy: Wrong and How to Right It” – at Union Theological Seminary. This was a “pilot” or “workshop” (12 hours over only two days) for what I hope becomes another of my ongoing pursuits, part of the “Institute” behind the Greater Good Initiative I previously wrote you about here and here.

I recently taught a new course – “Deep Policy: Wrong and How to Right It” – at Union Theological Seminary. This was a “pilot” or “workshop” (12 hours over only two days) for what I hope becomes another of my ongoing pursuits, part of the “Institute” behind the Greater Good Initiative I previously wrote you about here and here.

The origins lay in my dissatisfaction with most policy discussions today. We know a good deal about what works and what doesn’t in education, health care, criminal justice, and most major (domestic) issues: We aren’t failing to create better schools, or health coverage, or penal systems because we don’t know how, technically – we’re simply frozen ideologically. I’ve grown less enamored of studying, say, how to secure Social Security’s long-term solvency – it’s really not that hard! – and more interested in why we struggle over venality and insensitivity, generation after generation, millennium after millennium.

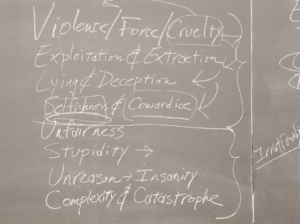

I spent the last several months reading extensively in fields relevant to this inquiry: game theory, evolutionary biology, behavioral economics, the study and practice of warfare. I was intrigued several years ago by a comment from a student of mine at Brown about “why societies go crazy” – Nazi Germany, for instance – which initially suggested psychological studies like the famous work of Stanley Milgram, but it also reminded me of the literature on complex-systems failures and disasters, which in turn are reminiscent of complexity and chaos in nature. Trying to distill and teach all this led to some thoughts I’d like to share … and hear your reactions:

-

-

Even the most counterproductive-seeming behavior is purposive.

-

I started with the notion of a spectrum of antisocial behaviors – ranging from the truly malign like killing or non-instrumental violence (“cruelty”), through less culpable behaviors ending in just-plain-stupidity. Turns out, it really breaks down into rational and irrational behaviors – and most bad behavior is actually rational. We all know that lying and deception are rampant in the natural world because they serve real purposes. It may be harder to see a value in, say, “cowardice,” but there actually is: In any lion pride, a certain percentage of lions charge into battle to risk their lives for the others, but there’s also a stable number of slackers – a pride needs both heroes with the courage to sacrifice for the greater good and self-serving cowards who survive, no matter what. The same basically holds true with cruelty: Even when it seems to serve no instrumental purpose, it almost always does (e.g., conveying intention and resolve).

-

-

Crazy ain’t so crazy.

-

As Peter Hayes discusses in his recent book, Why? Explaining the Holocaust, Hitler never achieved majority support, but was elevated to office through the cowardice and self-serving (if ultimately incorrect) calculations of other politicians as to their ability to control him. Once in power, the Nazis exploited terror and, again, rational if not-exactly-admirable cowardice to gain unwilling compliance. Taken together, it’s more a systems failure than mass insanity or depravity. There are other examples of “societies gone crazy” – such as China’s Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, a mass convulsion of fanaticism that killed more people than any other event in human history – but it turns out that there are instrumental reasons for fanaticism. And according to Thucydides, the entire population of Athens “went crazy” and abandoned all ethical norms in the plague that struck during the Peloponnesian War – because everyone knew they wouldn’t live long enough to be punished and so acted accordingly. Alas, all this is rational, if depressing. In fact, as we’ll see, nature essentially requires chaotic processes and outcomes.

-

-

Evil ye shall have with ye always.

-

I started this exploration hoping to find a path to eliminating bad outcomes, or at least reducing them. But both game theory and natural science suggest that – as the lions illustrate – a certain amount of “wrong” is required, almost as a physical rule. It is virtually impossible to construct any sort of stable system in which the actors – people, animals, or protons – behave in a consistently self-sacrificing manner. Of course, you can’t construct a stable system, either, in which exclusive self-interest totally prevails, either. A mix is required, and the socially-best mix will involve some pro-social (“hero lions”) and, ironically, some anti-social behaviors (“slacker lions”), with most of us falling somewhere in between. This did not really surprise the seminary students; I found it dispiriting, however, to conclude that wrong is, essentially, an immutable mathematical certainty. The best we can do is not so much eliminate “wrong” as to stave it off for another day, one day at a time. However:

-

-

You can’t put it off forever.

-

Perhaps, like Scheherazade in the Thousand and One Nights, we can so successfully forestall disaster one day at a time that this eventually becomes a permanent state. Unfortunately, that’s not likely. Chaotic systems in nature turn out to follow rules called “power laws” that predict the frequency and magnitude of disturbances: We know with a fair degree of certainty how often certain-sized earthquakes will occur – we just don’t know precisely when. Human events seem to follow similar power laws; as historian Niall Fergusson points out in his recent book, The Great Degeneration, these suggest we’re due for a 10.0 global political earthquake in about, oh, 2020. (That might be a good reason to re-read my piece from the eve of Trump’s election on the history of the 21st)

-

-

There are reasons for altruism.

-

Despite all these bleak observations on human behavior and social breakdown, people and animals living in situations in which it makes mutual sense to cooperate find ways to do so. This is usually enforced through social norms where those who fail to comply are sanctioned. Of course, people often try to get away with bad behavior when they think they can (as in plague-stricken Athens) – but many still engage in “moral” behavior even when they don’t have to, whether that’s because nature (or nurture) has programmed that into us, or because of a rational calculation that the short-term gain of norm-breaking isn’t as valuable as the long-term benefits of being part of a norm-abiding society. You can see that all the time in highway merges where some drivers “cut” the line but most still don’t – except that we know societies also reach “tipping points” where, if too many people “cut,” then everyone does so … leading to mass gridlock.

-

-

Maybe politics really is the answer.

-

I’ve spent my life in and around government, hoping to make both policy and political processes work better. But perhaps that isn’t the best way to make a difference – which is why I’ve focused more recently on things like the Greater Good Initiative, exploring deeper roots of social dysfunction, and social enterprises that might produce better societal outcomes. If, however, we can’t really rid the world of “wrong,” but only constrain and postpone dysfunction, perhaps a day at a time, it’s political and governance mechanisms that provide the means for doing so: Devising more “resilient systems” that can survive perturbations without spinning into chaos. Creating the communications and coordination that allow people to “escape” the Prisoner’s Dilemma and other game theory challenges. Or simply finding the compromises that let us stave off bad outcomes for one more day. So, maybe I’ve been in the right place all along….

-

-

A world without either communism or capitalism?

-

One thing I was not prepared for was how extremely liberal these seminary students turned out to be: I rarely find myself to be the most right-wing person in the room. Their righteous indignation at the economic and political mores of our times, however, forced me to revisit and rethink a lot of the “realities” I’ve come to accept. On the other hand, their vehement denunciations of capitalism reminded me of college debates back in my day with the Marxist and Third World sets – except that Marxism, socialism and the like never came up in this discussion. It was striking the extent to which truly leftist solutions have completely vaporized – even amongst these left-y and Third World students. The students’ proposed solutions seemed essentially to be to bring back relatively mild economic redistribution programs from the Sixties. But both the nation-state and global capitalism face serious challenges from new technologies; these technologies – changing the very nature of work, ownership and capital – will require an entirely new conception of economics.

-

-

Hackathon, anyone?

-

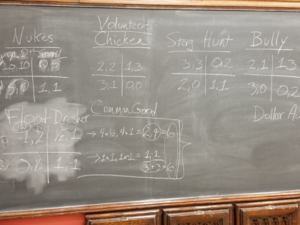

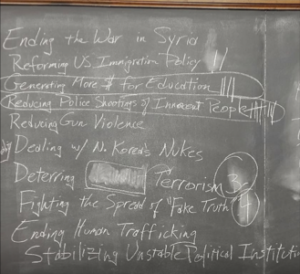

That brings me to my final, and most felicitous, discovery in teaching this course – that creative new ideas can be easily forthcoming if we just bring together committed people to discover them. In the most recent update I sent you, I discussed the plan for developing the Greater Good Initiative into, in part, a series of localized efforts to solve policy problems outside of the usual policy channels. The question is how best to do that; my concluding course segment might provide a good potential model – one I borrowed from the burgeoning “hackathon” phenomenon. We closed the course with two one-hour (all-too-brief) “policy hackathon” sessions, where the students chose from a list of intractable issues, split into small groups, spent 30 minutes brainstorming original ideas, then presented them to the class. While the students were bright and well-informed, they had no particular policy background or expertise – but in every case, and in short order, the groups produced innovative ideas unlike those coming out of think tanks and political parties today. Similar policy and social venture “hackathons” around the country are just the interactive process the Greater Good Initiative needs.

That brings me to my final, and most felicitous, discovery in teaching this course – that creative new ideas can be easily forthcoming if we just bring together committed people to discover them. In the most recent update I sent you, I discussed the plan for developing the Greater Good Initiative into, in part, a series of localized efforts to solve policy problems outside of the usual policy channels. The question is how best to do that; my concluding course segment might provide a good potential model – one I borrowed from the burgeoning “hackathon” phenomenon. We closed the course with two one-hour (all-too-brief) “policy hackathon” sessions, where the students chose from a list of intractable issues, split into small groups, spent 30 minutes brainstorming original ideas, then presented them to the class. While the students were bright and well-informed, they had no particular policy background or expertise – but in every case, and in short order, the groups produced innovative ideas unlike those coming out of think tanks and political parties today. Similar policy and social venture “hackathons” around the country are just the interactive process the Greater Good Initiative needs.

Well, at least one student took notes on my lectures….

Well, at least one student took notes on my lectures….

What do you think? I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments below.

“Are You Better Off?”

I just wanted to share with you my most recent piece for US News & World Report, which is also, sadly, my last, as they’ve discontinued their Opinion section. Watch for news on my new writing outlets soon.

I just wanted to share with you my most recent piece for US News & World Report, which is also, sadly, my last, as they’ve discontinued their Opinion section. Watch for news on my new writing outlets soon.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP last week launched an international trade war, hung up on Mexico’s president because he wouldn’t agree to pay for Trump’s border wall and announced he favored seizing guns without due process (a position from which he quickly retreated). These issues all have something in common (other than Trump) that goes to the root of what’s wrong in American politics today.

As discussed (here and here) during the 2016 campaign, both trade and immigration constitute a particular type of problem: Each benefits the larger society, raising the standard of living not just of the country as a whole but also of the majority within it. Yet both produce losers; various studies show, for instance, that immigration results in higher earnings for those with already-higher earnings – but lower wages for the lower-skilled.

Such “wedge issues” are used by politicians to drive Americans apart to the advantage of no one but these politicians. They are a means to exploit people’s misfortune by turning it into anger – and then turning that anger into votes. What they are not are exercises in building constructive solutions to problems, through compromise, consensus or common cause. And they are all traceable to the single watershed moment in which Ronald Reagan transformed American politics into the unrelenting exercise in selfishness that it is still today, when he asked Americans to vote on the basis of one question alone: Are you – not the country as a whole, or others, but you – better off today than you were four years ago?

Yes, politics is largely about self-interest, and even the Framers believed that a balance of self-interests, not messianic utopianism, was the central requirement of stable democracy. But the country’s leaders used to call us to a vision – even when the ultimate goal was individual freedom and self-realization – of an America greater than each of us individually. “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” died with “Are you better off?”

Trump is the apotheosis of this morally-denuded politics. Has there ever been a human being so clearly interested in nothing but himself? Despite his faux populism, his agenda in office has been a mix of standard-issue tax breaks targeted almost entirely to his fellow plutocrats and banana-republic self-enrichment. Even his conception of “making America great again” is about atomized self-interests, not any notion of an “America” embracing all, or even most, of us, knit together to form a society: A “greater good” beyond individual grievance? Global leadership? Moral values? As Robert D. Kaplan recent wrote in The National Interest (by no means a liberal publication), “[Trump] has also, with his calls for protectionism and a narrowly defined American self-interest, voided American foreign policy of any real, uplifting purpose – another sure sign of decline.” We are, in short, a country losing its way morally, one wallowing wholly in self-interest.

Whatever Trumpism’s underlying themes of racial, sexual and economic resentments, Trump has chosen trade, immigration and the demise of extractive industries as his chisels to break apart American society precisely because, while these have generated tremendous gains for the U.S. as a whole, they produce a subset who pay the price for the overall advance. Morality – as well as a practical regard for political reality and social peace – suggests that some of the gains of progress be redistributed to its victims; this might, in fact, be regarded as the core of “progressivism.” But as Democrats have become the “Party of the Ascendant,” those left behind by the world economy – largely older, white, religious, conservative males with lower levels of education living in rural or exurban areas – don’t seem all that appealing, or deserving of solicitousness, to “progressives” nowadays. In lieu of adequate solutions, Trumpism has been left to exploit the resulting unfairness and resentment to tear down both broader progress and all social cohesion.

This is exemplified in the current polarization over guns, as well, a point brought home by a Douglas High School student, Emma Gonzalez. Toward the end of her fiery speech with its refrain, “We call B.S.,” Gonzalez observed that the position of gun advocates appears to be that their rights to own guns outweigh children’s right to live. This has been a recurrent liberal argument since the Parkland shootings – but liberals ought to be wary of assertions that all rights must be balanced against other concerns: The rights to a fair trial, or against cruel and unusual punishment, or to free speech simply are not outweighed by governmental exigency or others’ sensitivities. Nonetheless, as I wrote after these shootings, most of us recognize and voluntarily concede non-governmental restraints on our rights in order to live in, and help produce, a functioning society with others. It’s called decency.

What’s striking about the gun debate today is the absolute unwillingness to seek the kinds of compromise necessary to a society, as opposed to an unwilling collection of individuals. We are no longer interested in anyone else’s perspective or anyone else’s rights. As Gonzalez summed up the situation, dismissively, “Mine! Mine! Mine! Mine!”

This phenomenon isn’t helped by Trump’s suddenly announcing that, as on so many other issues, the answer is to empower his own id and worry about constitutional rights later, if at all. We actually don’t need a Great Leader who believes that He Alone can solve our problems as a society – although that is an appealing solution to a growing, and scary, number of Americans. Rather, we need a society willing to solve its problems as a society.

It’s increasingly clear that we no longer live in such a world. We increasingly live, rather, in neighborhoods where no one disagrees, read news that doesn’t challenge our views, select our own definition of truth like we do our own music, and never have to adjust our preferences to those of anyone else. Neither politics, governments nor countries as we know them will last in such an environment. The question is whether such concepts as common good, or compromise, will.

You Can Do Anything

The other night, just after finishing my piece that ran yesterday on what we can do about gun violence, I received an email from a student at Princeton University, where I’d given a talk two weeks ago. It began;

“Thanks so much for coming to Princeton, firstly! The discussion with you is one of the best events I’ve ever been to at Princeton – you felt really accessible, personable, and I, at least, felt like I could do anything afterwards.”

That’s probably the first time anyone found me particularly “accessible” or “personable.” But what I talked about at Princeton was the work I’m doing outside my consulting to respond to the changes I see in the world today through the “Greater Good” initiative I’ve discussed here a bit, and my related efforts to launch a “government business.” Unlike most people I know, who think we’ve descended into a second Dark Age, I believe we’re entering a Golden Age for the ability of us all individually to – in Gandhi’s phrase – be the change you want to see in the world. That’s why this student – and the others who hung around afterwards to talk with me about career pursuits – rightly took from my remarks the feeling that he “could do anything.”

My piece yesterday in US News (which was also picked up by MSNBC) in reaction to the Parkland shooting discusses the same phenomenon behind my optimism about our ability to act – if at the same time, indeed because of, my declining belief in traditional politics as the best route for doing so. In People, Not Politicians, Can Solve America’s Gun Problem, I note that, “not surprisingly, mere days after the massacre at their school, students from Parkland watched from the gallery as their state legislature voted down holding any debate whatsoever on assault weapons this year. There almost certainly will be no meaningful government action against gun violence.”

I’ve used my US News platform to argue for several years now that “governments everywhere are growing in impotence due to a host of tectonic global shifts,” and, to me, what’s happening now over guns proves the point: A minority of Americans representing a return to extractive economics and politics now holds virtually unchallenged political power in the US – and increasingly around the world – yet the majority, who live in a very different world economically and ideologically, are rising up to wrest power from them on this issue, led by the least powerful of all: children. My argument is that this effort will continue to fail politically – but that is irrelevant. It will succeed through non-governmental means – and I give numerous examples: consumer boycotts, disinvestment campaigns, voluntary home interventions, public shaming, moral opprobrium, information and education, even (God forbid!) research. “A previous generation of young Americans ended a war and ushered in an era of greater tolerance by changing society more than by changing politicians. That’s where attention needs to be focused.”

This ties into the Greater Good, the “government business,” and a new series I’m writing for a national publication on what “progressivism” or “liberalism” need to mean in the 21st Century. New technologies are making it increasingly difficult for centralized authorities to assert and maintain their dominance – reducing marginal costs, lowering barriers to entry, making it easier for individuals to act on their own, and virtualizing virtually everything. These same technologies also make it quicker and easier to aggregate individuals, metricize and monetize virtually everything, keep free-riders out and enforce commitments amongst those who opt in. This isn’t eliminating all “authority,” but it is disaggregating, distributing, and disrupting what authorities already exist. This will prove just as true in governance as in every other industry.

This poses tremendous challenges to social cohesion, collective action and public goods through the mechanisms that have governed our world for centuries. But those mechanisms haven’t always existed as they are today, and they won’t exist that way in the future. Meanwhile, these changes present tremendous new opportunities for social cohesion, collective action and public goods through new mechanisms – like the student-launched social ventures I talked about recently here, like the non-political social movement we’re building with the Greater Good initiative, and even the business I’m launching to allow people voluntarily to invest in progressive “public goods” from education to health care and day care to income-transfer programs.

I’ll be discussing these in more detail in my next update. Meanwhile, all these changes are making it increasingly easy for anyone to follow the famous George Bernard Shaw injunction, “Some men see things as they are and ask why. Others dream things that never were and ask why not.”

As always, I welcome your comments below.

PS: In case you missed them, here are my other pieces in the past two weeks:

– A Time for Anger and The Limits of Tax Cut-mania in US News & World Report

– And History is Back is now available as the featured piece online from the latest Aspenia

Care and Concern

At the end of each year, I write a think-piece about the state of the world and where things are headed. This year, I was asked to write a longer disquisition than usual by Aspenia, the Aspen Institute’s European journal.

At the end of each year, I write a think-piece about the state of the world and where things are headed. This year, I was asked to write a longer disquisition than usual by Aspenia, the Aspen Institute’s European journal.

That’s now out and you can read the full version – Welcome to the History of the Future – below, but if you don’t want to plough through all of it, here’s the “Reader’s Digest” version: Despite Francis Fukuyama’s famous pronouncement 30 years ago that we’d reached The End of History, “history is back with a vengeance.” Unlike in the past, “[t]he relevant battles, however, will no longer be those between the public and private sectors, or between one nation-state and another: they will be a contest between the virtual or territorial, cooperative or extractive, consensual or coercive, and connected or chaotic.”

Over the last decade, the economy has slowly transformed into one where “clean” cognitive-based industries have mostly banished “dirty” extractive industries and mechanically-oriented work; traditional gender roles and sexual norms have been overturned; formal apartheid has been crushed; liberal internationalism has been declared the only global social system; and traditional warfare (at least between developed countries) has been largely abandoned. It’s shocking to see all that suddenly falling apart at the very moment of its seemingly-unchallenged ascendancy – only if you don’t notice that that’s pretty much how history works. Liberalism is today’s spent force, while reaction is seemingly in the ascendance.

Nonetheless, the very developments driving this crisis pose serious long-term challenges to the alternatives to open, liberal, democratic societies, as well. The crisis of faith across the world is driven by emergent technologies and their attendant double-edged challenges. These will only accelerate in the next decade or two…. The ultimate resolution will likely produce new forms of government, economics and social organization as different from today’s as our world is from the Middle Ages. No one yet knows what these will look like.

How should we respond to this reactionary moment? As I wrote recently in US News & World Report, I spent a good part of 2017 meeting and talking with opposition figures from such repressive countries: Russia, Turkey, Venezuela. One of them – Andrés Miguel Rondón from Venezuela – wrote an article in The Washington Post, “To beat President Trump, you have to learn to think like his supporters,” that everyone should read. As Andrés forcefully concludes, “Trump’s solutions may be imaginary, but the problems are very real indeed…. Showing concern is the only way to break the rhetorical polarization.” I elaborated on this in How to Stop Creeping Authoritarianism:

I would reframe Andrés’ argument in one respect: It’s not a matter of “showing concern” – like George H.W. Bush’s infamous pronouncement, “Message: I care” – where it’s obvious that it’s simply a message and you don’t. Rather, it’s a matter of actually caring.

Liberals and progressives think that by definition they care; like some sort of GEICO ad, “it’s what they do.” But the prototypical liberal response to the challenges of the changing world – train people for jobs more like yours, tell them to relocate to places like where you live, and end their benighted existence by forcibly imposing on them better values more like your own – is by no stretch “caring.” … Rather, as I noted here a few weeks ago, that’s always been the program imperialists impose on the conquered. Since when have progressives ever thought that morally defensible?

Simply attacking Trump and ridiculing his policies is insufficient. You can say all you want that Trump is lying about bringing back coal and manufacturing jobs – it will have no effect: His voters already know this. People aren’t stupid: They know he’s lying. They like that he cares enough to do so – to pay attention to and respect their concerns, and elevate them to the center of his agenda. That’s certainly more than effete liberals do.

I’m not suggesting fighting disingenuousness with more disingenuousness – I’m suggesting the need for honest concern.

I then offered several economic policy prescriptions with which progressives can start – which you can read in the original – and concluded:

Trump hasn’t done and won’t do anything on any of these fronts — and the GOP certainly won’t, either. Instead of criticizing that — and ridiculing voters for not “getting” it — there’s a better solution: Do something about it.

That is, if, as a so-called progressive, you honestly do care.

One thing you can do is to join in the Greater Good Initiative that I discussed in my last update and help us make a difference.

As always, I welcome your comments below.

Quick Links:

– How to Stop Creeping Authoritarianism

– To beat President Trump, you have to learn to think like his supporters

My pieces last year on:

Welcome to the History of the Future

Eric B. Schnurer

In the past year, the future has come into sharper focus. And it turns out, the future is … history. A quarter century ago, Francis Fukuyama famously wrote that we had reached “The End of History,” with “history” defined as an age-old struggle between repression and freedom, exemplified by liberal democracy, free markets, and human rights. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, both the ideal and reality of freedom had triumphed, and the historic struggle of humanity was completed.

In the past year, the future has come into sharper focus. And it turns out, the future is … history. A quarter century ago, Francis Fukuyama famously wrote that we had reached “The End of History,” with “history” defined as an age-old struggle between repression and freedom, exemplified by liberal democracy, free markets, and human rights. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, both the ideal and reality of freedom had triumphed, and the historic struggle of humanity was completed.

Now, it seems, history is back with a vengeance. The forces of authoritarianism, state-backed economic extraction, and violent intolerance are riding high, both across the globe and in an America that – at least in the Obama years – fancied itself as the liberal paradigm of the future. But the seeds of this seemingly-overnight reversal actually were sown well in advance, and the same, interrelated changes in technology, economics and ideologies mean that the age-old struggle continues. The relevant battles, however, will no longer be those between the public and private sectors, or between one nation-state and another: they will be a contest between the virtual or territorial, cooperative or extractive, consensual or coercive, and connected or chaotic. Welcome to the “history” of the future.

A NEW HOPE (AND CHANGE). Not so long ago, but in a country seemingly far, far away, the United States was a relatively homogenous place. It was not uniform, but it was relatively intermixed economically, socially, and politically (except, of course, in matters of race). Barack Obama’s 2008 election was not so much a departure, however, as the culmination of a large number of long-term demographic, political and economic transformations.

For the better part of a century, the Democratic Party had been the “Party of the People,” representing the interest of working class Americans against the more business-oriented Republicans; it was also a “big tent” party, embracing the disparate interests of conservative Southern whites, prairie populists, urban industrial workers, and, increasingly, racial minorities. (Even the Republicans were somewhat more heterodox than today, encompassing a large number of liberals, particularly on race, as well as far-right fringe elements.) But by a generation ago, Americans were beginning to sort themselves more rigidly by geography, with entire regions and even states largely devoid of one political party or the other. The same was true for such other socioeconomic factors as industrial composition, income distribution, religiosity, and lifestyle, all of which grew highly polarized and segregated by geography. Even while the nation grew remarkably more diverse racially and ethnically, it remained geographically polarized.

By the time of Obama’s election, the Democrats had been remade as a party of coastal, urban, well-educated, multicultural, and well-heeled elites. In contrast, and since Richard Nixon’s day, Republicans had been courting the white working class with appeals to a combination of economic, religious, cultural, and thinly-veiled (if that) racial anxieties. Whatever the emotional appeal, however, this Republican strategy didn’t produce any real support for “anti-government” policies favoring the elite – something Republican leaders didn’t realize until the Donald Trump phenomenon was upon them (and apparently still don’t realize now). The stage was set for both parties to lose their working class base – the Democrats to desertion, the Republicans to a hostile takeover. Moreover, while this analysis focuses on US politics, essentially the same can be said about developments elsewhere.

THE EMPIRES STRIKE BACK. The rising right-wing populism and authoritarian politics worldwide have engendered a continuing debate over whether these are driven by racism and other cultural concerns “or” by economics. In truth, these factors are intertwined.

THE EMPIRES STRIKE BACK. The rising right-wing populism and authoritarian politics worldwide have engendered a continuing debate over whether these are driven by racism and other cultural concerns “or” by economics. In truth, these factors are intertwined.

For nearly two generations, the economy has been moving away from skilled human labor, shifting to cognitive skills at one end of the spectrum and unskilled or, increasingly, non-human labor (a product of the cognitive-skill industries) at the other. Over this period, manufacturing regions have been hollowed out and essentially isolated in country after country – just as agricultural regions were during the Industrial Revolution. Those regions connected to this new cognitive economy have prospered, become more ethnically and culturally diverse, and grown closer together while tearing away from their traditional hinterlands. It is as if the continents had been rearranged – just not physically. Economic inequality between countries has been decreasing. But economic inequality within countries – virtually everywhere – has increased.

And all that was before the Great Recession. The Great Recession was this century’s equivalent of the Napoleonic Wars of the early nineteenth or Great War of the early twentieth – the shattering of the world order. Despite growing inequities, the post-Cold War world still supposed a meritocratic social contract under which those at the top at least cared about, and acted in the interests of, those below. The Great Recession destroyed what faith remained in that social contract: the elites – political, social and economic – not only acted in their own venal interest (both in bringing about the crisis and then in bailing themselves out at everyone else’s expense), but they also demonstrated that, when it came to running the world, they didn’t know what they were doing.

THREATENING DEVELOPMENTS. Not surprisingly, those on the outer fringes of these developments have viewed them as running counter to their interests; they see that those people benefiting from these developments (the elites) and their institutions – political, economic, cultural – decreasingly responsive to their needs. Democratic participation has been falling everywhere for some time, along with faith in government, the media, educational institutions, science, and even the idea of truth itself.

The technological changes underlying these developments are notably bringing radical disintermediation to virtually every industry. This makes the current technological revolution different from those of the past, which were centralizing and hierarchical. (The closest comparison might be the invention of moveable type, which made diffusion of knowledge less costly and more widespread, and eventually led to widespread translation of religious texts into the vulgate, the Protestant Reformation, the attendant birth of the nation-state, and the emergence of modern democracy.) Not only is such across-the-board disintermediating, democratizing, and distributing technology laying waste to industries (from publishing, broadcasting and music to real estate, retailing and finance), it is also necessarily changing the nature of wealth, war, and work – not to mention all forms of authority, including those related to expertise, or truth and meaning. It is erasing lines we have long drawn to make sense of our world, between the physical and ephemeral, ourselves and others, right and wrong, truth and falsehood, here and there.

Of course this is threatening to many. It has engendered a reaction: people are seeking refuge in strong states, territorial bulwarks, traditional values, ethnic demarcations, and even extractive (place-specific, non-virtual, low-cognitive) industries. Vladimir Putin’s kleptocracy, an increasingly-statist China, and the resurgent theocracy of isis have all been held out over the past decade as competitive alternatives, even by many in the West. Authoritarian leaders and parties, riding the wave of working class anger, have seized power and entered government around the world. Trump’s shredding of democratic norms, his administration’s promotion of an ethno-state with impermeable borders, and his abdication of global leadership to Chinese and Russian expansionism, it’s the Indian Summer of empire.

RETURN OF THE JEDI? Serious contradictions abound in this rising global reaction, however. Phillip Bobbitt has observed that “terrorism” in every age is simply the mirror image of the corresponding state structure it opposes. Today, the contending alternatives to the emergent power structures of the twenty-first century all reflect the “New World Order” they ostensibly oppose.

The rebellion against globalism is, in fact, global; the counter-revolution against connectedness is connected. The worldview and underlying economic realities of angry young jihadists, aspiring neo-Soviets, Euro-skeptics, and militant alt-right extremists in the United States are not only all remarkably similar, they are also all quite aware of that. Indeed, they are slowly joining in common cause. The contest thus is hardly between the globally-connected and the parochial – it’s between two emerging global parties.

The “alt” groupings, moreover, are not necessarily politically authoritarian (although they are decidedly anti-liberal and at best apathetic about democracy). Like the radical democratizing and distributed nature of the emerging technologies underlying all this, those who oppose the global direction of recent decades tend toward decentralization and libertarianism as much as the fascism of the past. As has been widely observed, Trump needs his followers more than they need him, and the vast bulk of them seem just as aware as his opponents that he’s a hollow fakir. They don’t empower him for his views, but because he empowers theirs. In many ways, then, the anti-elite movements today – radically democratizing and globally connected groups that reject all leaders and institutions – reflect those very technologies that are shaping the world of the future and against which they are rebelling.

In fact, the strong statists are only hastening the decay of nation-states against which they’re reacting. This is evidenced in the still-simmering subnational revolts in the uk, across Europe, and in both multiethnic democracies and autocracies in the developing world including in Russia and China. Nor is the us immune: “Progressive” states and cities are already increasingly bucking the federal government, both domestically and on the international stage. In this era of discontent, the discontentment hardly stops with the state.

THE FORCE AWAKENS. The European elite has satisfied itself that this post-recession populist nationalism is receding. American liberals similarly console themselves with the belief that Trump cannot possibly win re-election with such abysmal approval ratings (they believe he only won to begin with because of our quirky electoral college system). But this is dubious: Trump’s base is unwavering in its support, while the demographics that most oppose him – the young and minorities – tend not to vote. And there’s an old saying in urban American politics, “You can’t beat someone with no one”; right now the opposition has no one. Not only is there no Democratic contender with the stature, gravitas, appeal and message necessary to improve upon Hillary Clinton’s electoral performance – there is no real Democratic raison d’etre.

THE FORCE AWAKENS. The European elite has satisfied itself that this post-recession populist nationalism is receding. American liberals similarly console themselves with the belief that Trump cannot possibly win re-election with such abysmal approval ratings (they believe he only won to begin with because of our quirky electoral college system). But this is dubious: Trump’s base is unwavering in its support, while the demographics that most oppose him – the young and minorities – tend not to vote. And there’s an old saying in urban American politics, “You can’t beat someone with no one”; right now the opposition has no one. Not only is there no Democratic contender with the stature, gravitas, appeal and message necessary to improve upon Hillary Clinton’s electoral performance – there is no real Democratic raison d’etre.

In part, that’s because the late-twentieth century progressive program has largely triumphed. Over the last decade, the economy has slowly transformed into one where “clean” cognitive-based industries have mostly banished “dirty” extractive industries and mechanically-oriented work; traditional gender roles and sexual norms have been overturned; formal apartheid has been crushed; liberal internationalism has been declared the only global social system; and traditional warfare (at least between developed countries) has been largely abandoned. It’s shocking to see all that suddenly falling apart at the very moment of its seemingly-unchallenged ascendancy – only if you don’t notice that that’s pretty much how history works. Liberalism is today’s spent force, while reaction is seemingly in the ascendance.

Nonetheless, the very developments driving this crisis pose serious long-term challenges to the alternatives to open, liberal, democratic societies, as well. The crisis of faith across the world is driven by emergent technologies and their attendant double-edged challenges. These will only accelerate in the next decade or two. Advances creating new industries and occupations that generate tremendous wealth for many will also render obsolete large swaths of professions beyond the blue-collar jobs that have so far borne the brunt of change. Capital and credit will become easier to obtain and new ventures easier to launch, while the gains from these will be increasingly concentrated in the hands of a limited few who own the algorithms that represent the new capital. The returns on other labor are likely to decline. Ubiquitous distributed technologies will make it easier for anti-liberal forces to penetrate and “hack” connected, open societies, transforming the nature and territory of conflict. At the same time, it will become easier for individuals to undermine oppressive, centralized systems and regimes and to form their own communities of choice.

THE FUTURE OF HISTORY. The ultimate resolution will likely produce new forms of government, economics and social organization as different from today’s as our world is from the Middle Ages. No one yet knows what these will look like. Hopefully – whether virtual or territorial – the cooperative will prevail over the extractive, the consensual over the coercive, and the connected over the chaotic.

What is certain, however, is that history is only just getting going again.

I Need Your Thoughts

To kick off the New Year in a new way, I need your input on a new initiative.

To kick off the New Year in a new way, I need your input on a new initiative.

In coming weeks, I’ll be telling you about some new writing, teaching, and business activities. But all of these relate to my central concern that, in the years ahead, we need to think very differently about notions of common good, “public goods,” and governance. That’s where you come in.

A year or so ago, I pulled together a group from diverse backgrounds – government, politics, finance, non-profit, social venture, and technology – to brainstorm about these issues: With technology changing the ways we interact and make choices together as a community, a society, or even a planet, how can we define a new politics of common good beyond government? How do each of us pursue our commitment to this “greater good” – something bigger than our individual selves – in an increasingly atomized world?

What started as a small discussion group grew to over 100 on-going participants. And what interested them most was bringing even more people into this discussion – which produced the idea of a larger conference. That conference, the “Greater Good Gathering,” was held this fall.

Now, we need you.

The conference featured Martin Luther King III’s keynote address on “Doing Good in the 21st Century,” an opening panel led by former Delaware Governor Jack Markell on improving government today, experts on the future of democracy, and an exploration of how public and private sector innovation might solve the health care problem.

The heart of the conference was three panels thinking creatively across traditional categories of public, private and “social” enterprise:

One consisted of entrepreneurs behind for-profit (yes, for-profit) ventures to insure low-income families, to help families obtain public benefits, to help prisoners maintain family and community relationships, and to monitor the status of seniors living independently.

Another featured experts on how market forces are being tapped to increase social investment, shift “policy risk” from taxpayers to private investors, and induce large corporations to respond to issues like worker rights.

Another featured experts on how market forces are being tapped to increase social investment, shift “policy risk” from taxpayers to private investors, and induce large corporations to respond to issues like worker rights.

But perhaps the most enthusiastic group was the college students who had started self-sustaining enterprises to solve social problems:

– One student produces prosthetics for those in her native Viet Nam who have lost limbs from traffic accidents or landmines, at a fraction of market cost.

– Others started a business to speed the processing of rape kits.

– Another markets technology to help his fellow dyslexics with their reading.

– One uses food waste to produce insects that replace fish as chicken feed (reducing overfishing).

– Still another builds client relationship management software for homelessness service agencies.

These young people are truly inspiring – but, in the timeworn manner of entrepreneurs everywhere, they hadn’t set out to change the world, or to make a buck: They simply saw a problem and, instead of just asking why, asked “why not?” At one point, when I questioned the director of a social venture fund about what she thought the field would look like in a decade, her answer was that there would be no distinction between social enterprise and “normal” businesses: All businesses will be “social ventures” – promoting the greater good even while making a profit.

These young people are truly inspiring – but, in the timeworn manner of entrepreneurs everywhere, they hadn’t set out to change the world, or to make a buck: They simply saw a problem and, instead of just asking why, asked “why not?” At one point, when I questioned the director of a social venture fund about what she thought the field would look like in a decade, her answer was that there would be no distinction between social enterprise and “normal” businesses: All businesses will be “social ventures” – promoting the greater good even while making a profit.

Organizing the conference, I was struck by how many people – venture capitalists, former White House officials and Cabinet secretaries, non-profit leaders and intellectual innovators – asked me to keep them “plugged in” in a way that implied that this wasn’t just a conference, or a one-time event: Something about this notion of pursuing the “greater good” really struck a chord. People are looking for new paths for making a difference, seeking the social relevance many used to look for in government … somewhere other than government.

People have suggested to me various forms this Greater Good Initiative could take:

– A think tank – or “institute” – to address these issues (my original intention).

– Smaller conferences, more frequently, in a variety of locations.

– “Franchising” the Greater Good concept to anyone, anywhere who wants to stage similar, local conversations – like TEDx – or building local organizations for people to meet and plan, like MeetUp groups.

– Building a virtual national community and ongoing conversation online.

– A political movement.

– A foundation.

– A venture fund to support young (or even not-so-young) entrepreneurs in developing sustainable solutions to societal challenges.

– Maybe all these things.

– Maybe something else entirely.

What’s the best answer? I don’t know. But I’d like your help in figuring it out: What I do know is that we won’t advance the greater good if we don’t advance it together. Please visit my blog, or email me, so you can share your ideas – and get “plugged in” as we move forward.

Quick Links – Conference Videos:

Public Section Innovation: Can Government Be Saved?

Martin Luther King III: Doing Good in the 21st Century

Defending Democracy & The Future of the Public Good

Current Innovations in Social Venture

The Next Generation of Innovators

New Models of Economic Empowerment

Application & Illustration – The Future of Health Care Reform

Writes & Wrongs

I wrote a few days ago that I’ve had an unusually fecund several weeks, churning out nine articles for four publications (plus the comments Tom Edsall quoted extensively in the New York Times), expanding my writing “footprint” to additional platforms to address increasing concerns about the direction we’re headed. I’d like to share with you what I’ve been writing lately – starting with my return this week to The Atlantic.

“It’s the Grandparents Stealing From the Grandchildren” – a title drawn from a conversation I actually once had with Kurt Vonnegut – addresses an issue I’ve been writing about since my “master’s thesis” at the Kennedy School: entitlements spending. The piece has harsh things to say about both parties’ approach – although it finds the Republicans most disingenuous (the piece reached #1 on The Atlantic within a few hours of its posting):

Speaker Paul Ryan announced that “we’re going to have to get back next year at entitlement reform, which is how you tackle the debt and the deficit,” even as he began negotiations with his Senate counterparts over exactly how much they’re gleefully going to increase the very same debt and deficit….

Which begs the question, why would we “reform” entitlements in a way that delays the changes until the problem they are supposedly intended to address will be largely history, imposing draconian cuts on the future? This amounts, purely and simply, to forcing our grandchildren both to pay for our profligacy today and our parsimoniousness tomorrow — or, if you prefer, our liberality toward ourselves and conservatism toward everyone else.

The other pieces published so far also have provoked strong disagreement across the political spectrum – which I hope means they’re making more of a contribution than usual.

For starters, in Why Donald Trump is the most successful president in nearly a century, I argued that, while “Trump is widely viewed as dangerously inept, disengaged, uninformed, uninterested in governing, devoid of meaningful policy objectives, and possibly unstable,” nonetheless “in a short period of time he has implemented more of his agenda, and more thoroughly remade American government and the country as a whole, than any president since Franklin Roosevelt.” To see my whole catalogue of reasons for this assertion, please read the article; yet, as I conclude, “None of this may be good. But it’s time to stop denying his success.”